The Evolution of Various Types of Post-colonial States in Africa.

- July 16, 2021

- Political Economics, Regional Intergration, Sustainable Development

Contents

Introduction

With a dark history of socio-political and economic domination, Africa faces major challenges particularly on the economic front. In the quest to chart a way forward that rights wrong of an unjust past, while unlocking the possibilities and addressing the challenges of the day, without compromising the future generations’ capacity to meet their needs, (in the parlance of the 1987 Brundtland Commission Report); it is incumbent to explore robustly the evolutionary paths of the African state.

In calibrating the mosaic of the evolution of different types of state in post-colonial Africa, it is necessary to work with the classification of Africa states into these periods:

- Traditional precolonial (Up until the 19th Century)

- Colonial State (colonialism: end of the 19th Century up to World War 2)

- Colonial Valuation (World War two era up to 1960s)

- Post-Colonial (early 1960s up to 1980s: developmentalism)

- 1980s to Present day (Neo Liberalism)

Conceptual Framings of the State

In a Weberian sense, a modern state is a system of administration and law which is modified by state and law and which guides the collective actions of the executive staff. “…the executive is regulated by statute likewise, and claims authority over members of the association (those who necessarily belong to the association by birth) but within a broader scope over all actively taking place in the territory over which it exercises domination”. (Francisco, 2010)

On the other end Marx and Engels upheld the state the “…outcome of the rise of property system, classes and class antagonisms”. (Francisco, ibid)

This assignment is cognizant of the limitations of both the Marxian and Weberian conceptual framings of state (particularly in characterizing the African states and good governance) though some of their generic tenets are useful in this analytical exercise.

For purposes and the scope of this paper the “state” is conceived as the system of governance at a national level comprising principals, institutions, systems and policies that exercise control over the masses within a given territory.

The Traditional Precolonial State (Summary)

Despite the efforts of erasure by the imperialists bent of painting Africa as a jungle of savagery, pre-colonial African societies had their culture and forms of organization. Forms of organization ranged from segmented to centralized communal and rulership systems.

Bellucci (2010) notes, “For their part, centralized systems also preserve social stratifications, configured as casts or orders, and range from sultanates to kingdoms and States. The great West African empires, such as Ghana in the 8th Century, Mali in the 14th Century, and Songai and Bornu in the 16th Century, were organized politically on the basis of trade with the Arab world.”

The invasive misogyny of colonialism decimated a lot of Africa’s cultural, traditional and social order. Nonetheless some traditional governance systems such as kingdoms resurface in the post-colonial era, Kingdom states such as Eswatini have remained intact to date.

The Colonial State

From a socio-economic view point the colonial state constituted the following three dimensions. The first being forced cultivation that obliged rural dwellers to cultivate crops lie cocoa and cotton for “consumption” in the metropolis. The second dimension was that of forced labor. This entailed coerced enlistment for derisory wages in mines, plantations and infrastructure projects.

The third dimension was the scheme of drawing the natives into the money economy by a way of taxation. Taxes were required in the form of the colonizer a reality that forced natives to become wage earners through exploitative work or through trade. “This set of measures brought millions of Africans into the world economy, with-out immediately removing them from their domestic societies. This is how Africa was introduced into the world economy, and is what led the continent to a state of underdevelopment.” (Bellucci, ibid)

The tale of the colonial state was a social paradigm (the base and super structure in Marx’s terms) of natives exposed to a strange and domineering cultural world that remained to them, so near yet so far.

Colonial Valuation

With the end of second world war Europe was undergoing immense political and economic restructuring. The nascent phenomena of nationalism across various Africa states spurred Europe to rethink its economic future. In this era, Europe began to revisit the place of Africa in its economic chess board. Europe would jump onto the gravy train of “developing Africa” while the sole object was to create new markets for the metropoles in Africa.

This era was also marked by the statism of nationalism which according to Bellucci (ibid) was not a mere nationalism of combat but also a nationalism of government as nationalist leaders sought legitimacy from the populace. The era was also marked by the narrowly scoped National System of Innovation as most Africa states espoused a scientific and technological outlook. In problematizing the economic policies of the Sub-Saharan states René Dumont (1962 in Bellucci, 2010) observes, “…they were making large-scale investments with capital-intensive technology; that they were failing to respect local technologies or respond to the hopes and aspirations of Africans; that they were serving the interests of groups of the East or West; and that they were thus doomed to failure”

Commenting on the dissipation of the colonial valuation era Mwatha (2010) states, “The short-lived Colonial State of Valuation, for ontological reasons, could not be so democratic as was perhaps intended. Independences were granted, earned, or otherwise achieved. Where freedom of party affiliation and free elections were allowed, power changed hands, and generally the colonial powers gave way to pressures” (Mwatha, 2010).

In states such as Madagascar and Cameroon bloody repression raged on. Algeria saw an eight-year long war after 132 years of imperialism while armed conflict continued in former Portuguese colonies for fifteen years. (Bellucci 2010)

The Post-Colonial State

Propounded in the 1884-1885 Berlin Conference, Colonialism through a cloak developmentalism, had a ravaging impact in African states as well captured in Walter Rodney’s book’s title: “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”. Colonialism introduced a chasm between what can be classified as periphery nations and the center nations. Center nations boomed in industrial and economic development on back of Africa’s labour and natural resources, while the periphery nations were deprecated as mere producers of raw materials.

Understating the evolution of the post-colonial state in Africa must take into cognizance not only the historical exploitation of Africa but the impact colonialism had in the fabric of Africa’s value systems, indigenous knowledge systems and culture. Colonialists orchestrated class struggles, tribal conflict various genres of social declension in their bid to divide and rule. This phenomenon was epitomized by the Divide and Rule policy of the British in Zimbabwe, Nigeria, etc.

The Post-Colonial State in the Marxian Lens

The evolution of the post-colonial states in Africa is deeply shaped the colonial legacy of common amongst almost all countries in Africa. From a Marxian perspective we are have a useful lens with which to unlock the evolutionary paths of the post-colonial state.

In doing this it is important to acknowledge that socio-economic and political structures of the colony was informed by and large the machinations of the colonist and colonialist with regards colonial statecraft that rode on the contours of the metropole. Key to this foundational dimension of colonial states (whose relics and vestiges have shaped the evolution of the post state), is the fact that the colonizers had to create draconian systems and mechanisms that afforded them repressive control over the colonized masses.

“Its task in the colony is not merely to replicate the super- structure of the state which it had established in the metropolitan country itself. Additionally, it had to create a state apparatus through which it can exercise dominion over all the indigenous social classes in the colony.” (Nwankwo 2012)

The foregoing is fundamentally important in conducting diagnostics on the development/evolution of post-colonial state for in most cases the ideological paradigms of statecraft relevant to the object of extraversion, exploitation and oppression have been carried over into the post-colonial and modern African states which are still groping for meaningful economic independence.

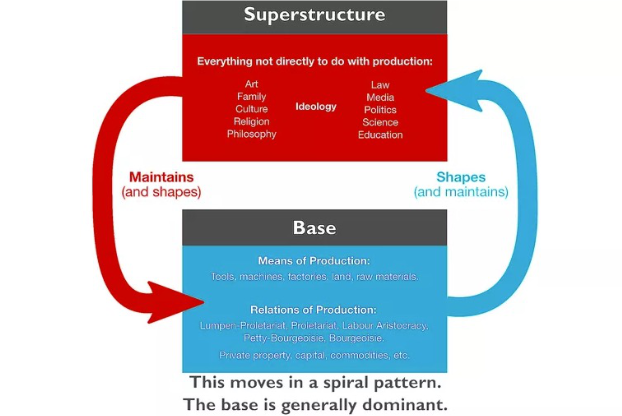

The Base and Super Structures

In a bid to understand the provenance of the over-developed apparatus of state and its machinery for controlling and regulating the masses the Marxian base and superstructure dialectic lays a formidable conceptual framework.

Figure 1: The Base and the Superstructure

Source:ThoughtCo (n.d.)

A society’s superstructure comprises ideology, culture, norms as well as identities that people espouse. This paradigm extends to social institutions, the state of the State (governing apparatus) and political structure. On the other end the base consists of the means of production as well the as relations of production. In the quintessentially Marxist perspective, the superstructure of the post-colonial African states is an embodiment of the interests of the ruling class, this is the relic of the colonial sociological paradigm.

“The colonial state is therefore equipped with a powerful bureaucratic-military apparatus and mechanisms of government which enable them through its routine operations to subordinate the native social classes.” (Nwankwo, ibid)

Using the above paradigm we can meaningfully map the configurations of most post-colonial African states to the “over-developed” super structure set up in the colony, whose roots lie in the metropole (the so called colonizing mother city). The independence of the colonized states is marked the separation (albeit more politically that economically) of the colony from the metropolitan.

Rent Seeking in the Name of Developmentalism

The Marxian lens, useful as it is, cannot be upheld as the holy grail of explicating the evolution of the post-colonial states in Africa. A trend that can be observed across many post-colonial African states is political economic phenomena of rent seeking. Rent-seeking is viewed in public choice theory and economics as means of increasing one’s wealth without necessarily creating new wealth. It could be viewed as means to accumulate wealth where there no value creation that warrants the increase of wealth or the quest for the increase. This is a phenomenon that can be observed in most post-colonial African states with the Eskom case and other state capture projects that have warranted the establishment of the State Capture Judicial Commission of Inquiry of South Africa. The practice plays out through the machinations of vote-maximizing political principals who may run into with budget maximizing bureaucrats.

Alavi cited in Beekers (2012) notes: “The state in the post-colonial society directly appropriates a very large part of the economic surplus and deploys it in bureaucratically directed economic activity in the name of promoting economic development”.

This is one dimension in which the evolution of the post-colonial state detracts not only ideologically from Marxist sociological theory but the colonial legacy as it rooted, by and large, in the post-colonial production processes. Beekers concurs: “The apparatus of the state, furthermore assume(s) also a new and relatively autonomous economic role, which is not paralleled in the classical bourgeois state.” (Beekers, ibid)

Citing the Comprador Theory Bjorn (n.d.) characterizes the post-colonial state as a comprised of sub-par bourgeoise type of middlemen or “compradors” who thrive on collecting fees and commissions for mediating market access to former colonies for former colonizers in a fashion that stifles the instrument of developmental state.

Patrimonialism and Neopatrimonialism

Patrimonialism and Neopatrimonialism have been conspicuous markers of the post-colonial state. The emergence of the patron-client networks was central to the modus operandi of mostly presidential post-colonial African states wherein power is concentrated on the ruling individuals (presidents) and their networks. Neopatrimonialism was also considered as a necessary means for post-colonial states to unify fragmented societies and foster redistributive economic development. “Neopatrimonialism is not seen as a synonym for corruption, but a distinct form of acquiring legitimacy and of dealing with difficulties in statecraft specific to Africa deeply rooted from pre-colonial times.” (Francisco, 2010)

In most post-colonial African states, the jurisprudential frameworks (law and constitutional) were upheld by patrimonial fashion which breeds clientelism, prebendalism, cases in which most public office bearers misappropriate public resources for private benefit.

Neoliberalism

The failure of the post-colonial developmental state ushered most African states into the neo liberal era, starting from the 1980s up to the present day. The international policy of the day brandished the strengthening of democracy (this was attractive for the weak and the still states), promoting of governance, improving the legitimacy of the governments in developing country. These became the much-vaunted hallmarks of thriving governance and as such most countries fell for the neoliberal entrapments that came with this framework referenced by Castells (2002) in Bjorn (n.d.) as the predatory model. The transition into the neoliberal state by most African countries was also influenced by the burgeoning liberal economies and states such as Germany, USA and the United Kingdom. This era was marked by the various Economic Structural Adjustments Programs by International Monetary Fund which saw heavily reduced public expenditure while leaving a lot of Africa states incapacitated by heavy debt to the IMF and other international financial bodies. This era saw the slump of GDP growth in Sub-Saharan Africa, slump in capital accumulation as well as the drying up of foreign direct investment.

“Between 1980 and 1989, 241 adjustment programs were carried out and became part of the prevailing ideology of the countries of Sub-Saharan African.” (Bjorn, n.d.)

National Systems of Innovation

A National Systems of Innovation can be defined as interrelated work of institutions that collage to originate, exchange, disseminate and adapt new knowledge. The fundament of this principle is the concept of innovation in its broader conceptions. A system of innovation can thus aggregate at a local, national or supra national level. As noted earlier, the post-colonial states were characterized largely by neoclassical and neocolonialist form of innovative approaches. The era was marked by heightened science and technological awareness. As such the Marco economic paths took by many post-colonial states was the narrow (Science and Technology) confined concept of innovation even at national policy level.

Manzini (2012) notes aptly: “The concept (of NSI) originated from the countries of the North as an ex post concept, whereas for most developing countries it is an ex ante concept. This fact means that in the developed world, the concept was built on the evidence of empirical data while in the developing world only a few countries fit the broad description of the NSI.”

Decentralization

The narrative of the evolution of the post state in Africa is not complete without considering the work of the African Union, the main body holding African states together after the dissolution of the Organization of African Union 2002. In 2014, AU ratified the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development. This was a major step in fostering local economic development through developmental statecraft. The main object of the charter, among a host of deliverables, is to promote devolution (decentralization) as a formidable vehicle of eradicating poverty (Sustainable Development Goal number one) through galvanizing states for local economic development. It must be noted that most AU member states have not yet ratified the charter and this is a cause for concern for a continent plagued by weak state, corruption and lethargic pace of transformation and sustainable development.

Conclusion

Regional Economic Integration, in the mold of Regional Systems of Innovation, is the only formidable way that African states that leverage their strengths and attain much needed economic development and stability through the economies of scale. This is the only way Africa can leapfrog hurdles of still-born national systems of innovation, rampant corruption, failed developmental statism and systemic failures by the super structure entrusted to midwife the transition of Africa from poverty, hunger and instability to prosperity, food security and economic stability.

References

Beekers D, B. van Gool. 2012.From patronage to neopatrimonialism: postcolonial governance in Sub-Sahara Africa and beyond. ASC working paper. (Available: https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/19547) [Accessed 18 December 2020]

Beckman Björn.n.d The Post Colonial State: Crisis and Reconstruction. (Available:https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/20.500.12413/10415/IDSB_19_4_10.1111-j.1759-5436.1988.mp19004005.x.pdf;jsessionid=D829352ED511B56DBF850BA83788FA44?sequence=1) [Accessed 19 December 2020]

Bellucci Beluce.2010. THE STATE IN AFRICA. (Available: http://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/bitstream/11058/6341/1/PWR_v2_n3_State.pdf) [Accessed 18 December 2020]

Bondarenko, Dmitri. (2015). Nation-Building and Historical Memory in Postcolonial States: Tanzania and Zambia Compared.

Chigwata, Tinashe & Ziswa, Melissa. (2018). Entrenching Decentralisation in Africa: A Review of the African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law. 10. 10.1007/s40803-018-0070-9.

Francisco, Ana Huertas (January 24, 2010). “To what extent can Neopatrimonialism be Considered Significant in Contemporary African Politics?”. Neopatrimonialism in Contemporary African Poltics.

Larson, Erik & Aminzade, Ron. (2009). Nation-building in post-colonial nation-states: The cases of Tanzania and Fiji. International Social Science Journal. 59. 169 – 182. 10.1111/j.1468-2451.2009.00690.x.

Makki, Fouad. (2015). Post-Colonial Africa and the World Economy: The Long Waves of Uneven Development. Journal of World-Systems Research. 21. 124. 10.5195/jwsr.2015.546.

Manzini T. Sibusiso. 2012. The national system of innovation concept: an ontological review and critique, (Available: http://www.scielo.org.za/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0038-23532012000500013) [Accessed 20 December 2020]

Settles, Joshua Dwayne, “The Impact of Colonialism on African Economic Development” (1996).University of Tennessee Honors ThesisProjects.https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/182

Stephen Ocheni, Basil C. Nwankwo (2012). Analysis of Colonialism and Its Impact in Africa. Cross-Cultural Communication, 8(3), 46-54. Available from URL: http://www.cscanada.net/index.php/ccc/article/view/j.ccc.1923670020120803.1189DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3968/j.ccc.1923670020120803.1189.

ThoughtCo.n.d.Definition of Base and Superstructure. (Available:

https://www.thoughtco.com/definition-of-base-and-superstructure-3026372) [Accesible: 18 December 2020] THE STATE IN POST-COLONIAL SOCIETIES : TANZANIA John S. Saul

A Developmental Economist.

ThinkTank

The core business of ThinkTank is to assert fundamental human rights across all societal fronts, through incisive and educative critiques on wide ranging socio-political and economic issues in Southern Africa, Africa and the world over.