Planet of the Humans: Untangling the Capitalistic Framing of the “Green” Movement

- June 3, 2021

- Political Economics

From the immigration rights in the USA, through drug policy reform in Brazil to non-violent resistance in Palestine the world has witnessed the power of documentaries to shape movements and yield change. While the power of documentaries to build social change infrastructure, impact public policy and rewire perception is indubitable, (Bacha, 2015), not many would have anticipated the incisive polarizing scoop parading the shameful pageantry of the much-vaunted green movement in the documentary, “Planet of the Humans”, narrated by Michael Moore, produced and directed by Jeff Gibbs. The documentary spotlights how the power matrix of grand standing politicians (Obama Barack, Al Gore, et al), cunning capitalists and corporates have been coopted into the so-called green movement that ostensibly purports to champion a paradigmatic shift from fossil fuels into climate and environment friendly renewable energy when in actual fact most of the renewable energy flagship “innovations” (solar, biomass, wind, etc) are produced through and propped by fossil-fuel intensive resources and activities which continue to deplete global hectares and biocapacities at scale. Through the lens of Southern Perspectives, dialectical materialism and decoloniality this paper presents a critique of the documentary on the climate change crisis.

Contents

Economic Growth versus Economic Development

The green movement has been reprehensibly touted for its imaginary and ostensive deliverables, green jobs and reduced carbon footprint. Somewhere in the documentary, climate activist Vandana Shiva makes a cogent and sobering observation:

“Our minds have been manipulated to give power to illusions. We shifted to measuring growth not in terms of how life is enriched, but in terms of how life is destroyed.” (Planet of the Humans, 2020)

The seduction of the masses on the false economic deliverables of the green movement are a microcosm of the upward trajectory of the global economic growth from the 1950s up. From the 1950s to date the global economy has been on an upwards trajectory in terms of Real GDP and Foreign Direct Investment (FDI). Real GDP and FDI are quintessentially metrics of economic growth than they are indices of economic development. In the same capitalistic playbook, masses have been fooled by the optics of the green movement which is hardly green nor a progressive movement.

Economic growth is limited to the increased output in goods and services produced by an economy at a given period in time while economic development comprehensively spans both qualitative and quantitative growth of the economy. (EDUCBA, n.d.)

In other words, economic development is a more meaningful measure of advancement than economic growth as it “…measures all the aspects which include people in a country become wealthier, healthier, better educated, and have greater access to good quality housing.” (EDUCBA, ibid)

The documentary has achieved an important step in illuminating the perversion of measuring advancement by how much life is destroyed (environmentally detrimental economic growth) as opposed to how life is enriched (environmentally friendly economic development).

Decoupling Infinite Growth from Environmental degradation

Despite the sterling effort of expose the fallacies of the green movement, towards the end of the documentary Gibbs unfortunately commits a conceptual error in inferring the idea that infinite growth on a finite planet is a form of collective suicide. The concept of infinite growth boarders on the economic growth (as opposed to economic development, as enunciated earlier). In the quest to calibrate the gravitas of the crisis confronting humanity, cognitive hygiene is still necessary for decoupling economic growth from environmental degradation. Gibb’s sentiments stem from an erroneous equating of economic growth with environmental degradation. Johnston Matthew (2019) concurs that despite the close historical connection between economic growth and environmental degradation, “…What is needed, however, is to turn theory into actuality by decoupling, or separating, economic growth from unsustainable resource consumption and harmful pollution.”

Ecological Epistemicide

Epistemicide denotes the obliteration of knowledge systems (epistemes). This practice undercuts the tenets of knowledge democracy that upholds diverse epistemes, indigenous knowledge systems, spiritual and land-based systems, etc. (Hall et al, 2017) The geopolitical locus of the documentary attests to this systematic ecological epistemicide which deliberately pushes Africa, Asia and other extra-western geographies out of the picture and downplays the damage these geographies have suffered in the context of western imperialism and continued extraversion while diminishing the endogenous contributions of these societies to environmental conservation and fighting climate change.

“…First, the understanding of the world by far exceeds the Western understanding of the world. Second, there is no global social justice without global cognitive justice. Third, the emancipatory transformations in the world may follow grammars and scripts other than those developed by Western-centric critical theory, and such diversity should be valorized.” (Santos, 2014)

In relation to Santo’s categoric insights on epistemicide, one of the important exercises in critiquing the documentary is to problematise “western centric political imagination and critical theory” to borrow the parlance of Santos. He puts aptly that there can be no justice at any level if transformation is not predicated on cognitive justice, the defining fundament of ecological epestimicide. While Jeff Gibbs has produced a rude awakening work in form of the documentary, the Westernisation of the climate change phenomenon in the documentary and in the mainstream needs to be deconstructed on two additional layers: The framing of the climate crisis and the crafting of the solution.

In an insightful critique of the documentary Halstead (2020) laments the over reliance on fossil fuels and echoes that when the fossil fuels run out the world will be forced to return into pre-industrial levels of climate and environmentally friendly technology. This one of the many areas where African communities and other non-western societies have led from the front. To this end, Ajayi et al (2017) corroborates:

“Over the millennia, local communities have relied heavily upon their IK to conserve their environment and deal with natural disasters. The communities, particularly those in hazard-prone areas, have developed a good understanding and knowledge of disaster prevention and mitigation, early warning, preparedness and response, and post disaster recovery. This knowledge is based on facts that are known or learnt from experience or acquired through observation and practice and is handed down from generation to generation.” (Ajayi, et al, 2017)

In light of the foregoing, the framing of the redress and recourse for climate change as an American or European project is unfortunate. Also, the delimitation of the Anthropocene to the American “Capitalocene” (Moore, 2015) is scandalous as this abstract from the global geopolitical, historical and political-economic realities of the modern world.

Dialectic Materialism

From a Marxist or Marxian lens, the locus of the of the problematique is cast in a dialectical materialistic Western Capitalism which is useful for demonstrating the interplay of socio-economic and political dynamics as engendered and driven by the material ends of largely, the capitalists. The cobweb of the machinations by the capitalists (billionaires, bankers and investors) as particularly epitomized by Michal Bloomberg roping in new investor (Jeremy Grantham) a billionaire timber investor in the Beyond Coal campaign when there is no real movement beyond coal is an important cadence in the microscopic exposition. The documentary presents an important opportunity to decipher capitalism “as both producer and product of the web of life, as a “rich totality of many determinations” that transcends the Nature/Society divide” (Moore, 2015). From this view point we can appropriately comprehend capitalism as world ecology that pits capital accumulation, pursuit of power and the co-production of nature as a whole.

Notwithstanding, the deafening silence on how the West has ravaged Africa’s resources and environment and inevitably its socio-economic and political fabric, is not only conspicuous but treacherous. But of course, the erasure of Africa and all non-western indigenes in mainstream epistemes and narratives is the calculus of coloniality and ecological epistemicide whose end is to cast the West as “global” and thus delimit the Anthropocene to a mere West-centric geo-polity.

The Overpopulation Myth

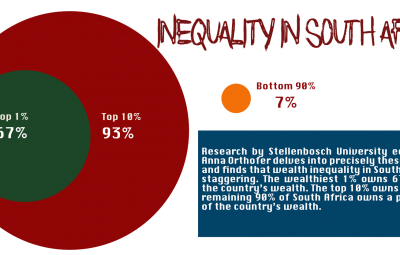

The critique of the documentary would be remiss if it left unattended the overpopulation myth. In the documentary various experts raise the issue of over population as the not only the elephant in the room but the “herd of the elephants in the room”. (Anthropologist Nina Jablonski from Penn State University) Unfortunately, the documentary misses the mark on this dynamic. Most activists have been propagating the dangerous narrative that overpopulation is the main driver of the planet’s ecological woes. For example, renowned primatologist Dr Jane Goodall remarked at a certain event (Heather, 2020) that population growth is responsible for our ecological crisis. The argument may sound quite harmless, yet it plays to, and taps from dangerous and toxic theories of Malthusainism. Robert Malthus erroneously postulated that population growth is potentially exponential while the growth of the food supply or other resources is linear. His work has influenced the shift into social Darwinism and eugenics, “…resulting in draconian measures to restrict particular populations’ family size, including forced sterilizations” (Shermer, 2016). Also, the interpretation of the ecological crisis as an overpopulation problem leads to a mischaracterization of what the roots of the problem really are and what solutions must be put forward. Data (Roser et al, 2019) shows that contrary to the overpopulation narrative, global population is not growing exponentially but it is rather slowing down and poised to stabilize around 2100. (Heather, ibid) Most importantly, there must be consideration of the fact that much of the poverty, inequality and environmental degradation in our world is not an outcome of overpopulation but rather a result of lopsided distribution of resources, an exploitative capitalistic economy that is bent on profit accumulation at the expense of human welfare. The documentary thus missed an important opportunity to debunk the overpopulation myth and put the finger right on the pulse of the real drivers of the looming climatic cataclysm.

The Ontology of Development

Notwithstanding some flaws in the ideological and theoretical framing of the documentary, it is however crucial to acknowledge that the documentary implicitly spurs us to ask the crucial ultimate questions: What then is sustainability? By extension, what is Local? and what is Development?

Answering these questions demands that we probe further and raise ultimate corollary questions in the quest for deeper meaning. At the core, we need to ask, what is the ontology of development? What does development mean? Is it still development if it not sustainable? Can change or innovation (the green movement) be rightfully termed “development” if it is not sustainable? For example, if we find ways that work to improve human lives for the next 500 years, but those ways cease to work beyond the 500 years should that be termed development. What if the innovations work for a million, or trillion years but cease to yield beyond then or prove to have been counterproductive or detrimental to the environment? would such innovations be rightly termed as development for the duration they seemed to work? The definition of sustainable development by the Brundtland commission posits a cogent answer to this conundrum: Sustainable development is, “development which meets the needs of current generations without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs” (WCED, 1987).

In light of Brundtland’s commission conception of development, the phrase, “sustainable development” is arguably rendered tautologous and by the same token, the mischaracterization of green movement fallacy as “untenable advancement” leads us to the incurable oxymoron of “unsustainable development”, since for any development (positive change or innovation) to be conceived as “development” it must intrinsically, implicitly, ontologically and inevitably be sustainable.

Conclusion

Armored with the epistemological deliverables of decoloniality, and armed with intellectual hygiene of cognitive justice, dialectical materialism and various theoretical frameworks that emerge from a lens of de-contaminated knowledge democracy, theory and praxis on sustainability must, while acknowledging the seismic, albeit Western-centric, contributions of the documentary, shift into a robust paradigm that espouses thinking globally while acting locally.

A “glocalised” consciousness on sustainability that is more dialectic that it is dualistic (nature-in-society dialectic as opposed to nature and society dualism in the besmirched Marxian metabolism metaphor (Moore, ibid)), will yield rigorous theoretical and practical approaches that recognize different and diverse forms of knowledge and knowing, including the long marginalized Indigenous Knowledge Systems (epistemes) of non-western indigenes. This is the much-needed bedrock for a realistic prospect of sustainable local development: the inalienable unitary building block of global (planetary) sustainability as encapsulated in United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (UN, 2016).

While the documentary by Gibbs is not necessarily exhaustive, neither does it cover the full gamut of the planet’s sustainability woes nor does it proffer any solutions, the biopic hits home through problematizing the valorized environmental solutions and questioning the canonized answers as well as challenging humanity to rethink not only the entire green movement travesty but to revisit the ontological, philosophical and ideological underpinnings of sustainability.

References

Abrell, E., Bavikatte, K.S., Cocchiaro, G., Jonas, H. and Rens, A. (2009) Imagining a Traditional Knowledge Commons:A community approach to sharing traditional knowledge for non-commercial research. Rome: International Development Law Organization.

Ajayi, Oluyede Olu & Mafongoya, Paramu. (2017). INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE SYSTEMS AND CLIMATE CHANGE MANAGEMENT IN AFRICA.

Alberro Heather.2020.Why we should be wary of blaming ‘overpopulation’ for the climate crisis. Available: (https://theconversation.com/why-we-should-be-wary-of-blaming-overpopulation-for-the-climate-crisis-130709) Accessed: 19 May 2021.

Bacha Julia. 2015. Why documentaries still have the power to change the world. Available: (https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/05/why-documentaries-still-have-the-power-to-change-the-world/) Accessed: 24 May 2021.

Boaventura de Sousa Santos.2014. Epistemologies of the South. Justice against epistemicide. Available: (https://iks.ukzn.ac.za/sites/default/files/Epistemologies_of_the_South%20(1).pdf) Accessed: 18 May 2021.

EDUCBA.n.d.Economic Growth vs Economic Development. Available: (https://www.educba.com/economic-growth-vs-economic-development/) Accessed: 19 May 2021.

Hall, B.L. and Tandon, R. (2017) ‘Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education’. Research for All, 1 (1), 6–19. DOI 10.18546/RFA.01.1.02.

Halstead John.2020.Damn dirty humans!: Planet of the humans and progressive denial [Critique and video documentary] Available (https://abeautifulresistance.org/site/2020/5/5/damn-dirty-humans-planet-of-the-humans-and-progressive-denial) Accessed: 22 May 2021.

Jason W. Moore. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life. Verso.

Johnston Matthew. 2019. Is Infinite Economic Growth on a Finite Planet Possible? Available: (https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/120515/infinite-economic-growth-finite-planet-possible.asp) Accessed 24 May 2021.

Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, Esteban Ortiz-Ospina.2019. World Population Growth. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/world-population-growth. Accessed: 22 May 2021

Meyer, Danie. (2014). Job Creation, a Mission Impossible? The South African Case. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences. 5. 10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n16p65.

Planet of the Humans.2020. Available: (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Zk11vI-7czE) Accessed: 14 May 2021.

Shermer Michael.2016. Why Malthus Is Still Wrong. (Available from: https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/why-malthus-is-still-wrong/) [Accessed, 2 May 2021]

UN.2016.The 17 sustainable development goals (SDGs) to transform our world. Available: (https://www.un.org/development/desa/disabilities/envision2030.html) Accessed: 24 May 2021.

A Developmental Economist.

ThinkTank

The core business of ThinkTank is to assert fundamental human rights across all societal fronts, through incisive and educative critiques on wide ranging socio-political and economic issues in Southern Africa, Africa and the world over.