Characterizing Poverty In Africa: Why Economic Growth Alone is not Sufficient to Solve the Plague of Poverty

- February 14, 2020

- Political Economics, Politics & Society

Since time immemorial, the endemic scourge of poverty has almost invariably, been synonymized with Africa. Africa’s paradox is that the continent is endowed with substantial natural resources in forms of minerals, flora and fauna and vast tracks of arable fertile lands, yet the continent is the poorest of all continents in the world. This has led to the argument that Africa is not poor but has been made poor.

This paper aims to underscore that, while there is need to grow Africa economies in view of the typical merits of economic growth, economic growth alone is not sufficient to curb the plague of poverty in Africa. The discourse necessitates a characterization of the causes and drivers of poverty in Africa, a collage of which serves to illuminate the inefficacies of parochial conceptions of what has been, in some circles, termed, “jobless” economic growth popularly punted as the panacea to the pandemic of poverty in Africa.

As can be gleaned from a few insights cited below, mainstream economics and developmental spheres are awash with poverty eradication ideologies premised on the hidebound and barren conceptions of economic growth.

“Historically nothing has worked better than economic growth in enabling societies to improve the life chances of their members, including those at the very bottom.” (Dani Rodrik, 2007)

In a report, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), concurs with the above:

“Economic growth is the most powerful instrument for reducing poverty and improving the quality of life in developing countries.” (OECD, No year provided)

The paper seeks to problematize the notion that economic growth is the remedy to the problem of poverty particularly in Africa as alluded to in the notions proffered above. The nub of the argument is that the array of drivers, causes and sustainers of poverty in Africa are way too complex and too structural to be effectively redressed from mono-dimensional and constricted frameworks of economic growth based development. In conclusion a case is made for holistic trans and interdisciplinary approaches to developmental economics that are attune to the bearing that other critical factors have with regards to how far economic growth can yield results in the quest for poverty reduction in Africa.

Contents

Definitional Assumptions

What is Poverty?Etymologically, the word “poverty” or “poor” stems from the Latin word “pauper” which means “poor”. The word “pauper” has its origins in the Latin words “pau” and “pario” which translate to: “giving birth to nothing”, a notion that references unproductive livestock and farmland (Jon Westover, 2008).

The definition of poverty, which has been widely adopted in various disciplines and bodies of knowledge, is based on looking at poverty from strictly economic terms. According to the World Bank, anyone who earns less than $1.90 a day is classifiable as poor. Notwithstanding, the World Bank strives to broaden the conceptualization of “poverty” by going beyond the technical remit of the definition:

“Poverty is hunger. Poverty is lack of shelter. Poverty is being sick and not being able to see a doctor. Poverty is not having access to school and not knowing how to read. Poverty is not having a job, is fear for the future, living one day at a time. Poverty is losing a child to illness brought about by unclean water. Poverty is powerlessness, lack of representation and freedom.” (Economic and Social Inclusion Corporation 2008- 2009)

The second definition will be useful in illuminating the inefficacies of mono-dimensional economic growth as the holy grail of development and poverty eradication in the African continent.

Defining Economic Growth

Various definitions have been given from all the proverbial corners of the world of the knowledge.

Economic growth is largely viewed as a comparative increase in the capacity of a given economy to produce goods and services. In this purview, economic growth can thus be measured in nominal or real terms wherein real terms can be adjusted for inflation.

“Traditionally, aggregate economic growth is measured in terms of gross national Product (GNP) or gross domestic product (GDP), although alternative metrics are sometimes used…..” (Investopedia, Economic Growth, 2019)

Bjork, Gordon J. (1999) posits,

“Economic growth is the increase in the inflation-adjusted market value of the goods and services produced by an economy over time. It is conventionally measured as the percent rate of increase in real gross domestic product, or real GDP.”

According to Bjork, growth in the is measured in real terms: “i.e., inflation-adjusted terms – to eliminate the distorting effect of inflation on the price of goods produced. Measurement of economic growth uses national income accounting.” (ibid, 1999)

The underpinning tenet of all the conceptions and definitions of economic growth is comparative growth in the capacity of a given economy to produce goods and services.

The following insights by Romer Paul (1990) are useful for redefining economic growth and particularly locating the improvement of quality of life at the center of the conception while underscoring that, rather than deriving from doing more of the same, economic growth rather derives more substantively from better and exponential ways of achieving the same goal.

“Economic growth occurs whenever people take resources and rearrange them in ways that are more valuable. A useful metaphor for production in an economy comes from the kitchen. To create valuable final products, we mix inexpensive ingredients together according to a recipe. The cooking one can do is limited by the supply of ingredients, and most cooking in the economy produces undesirable side effects. If economic growth could be achieved only by doing more and more of the same kind of cooking, we would eventually run out of raw materials and suffer from unacceptable levels of pollution and nuisance. Human history teaches us, however, that economic growth springs from better recipes, not just from more cooking. New recipes generally produce fewer unpleasant side effects and generate more economic value per unit of raw material….”

Romer, Paul. “Endogenous Technological Change.” Journal of Political Economy 98, no. 5 (1990): S71–S102.

In his ground breaking work, “The Art of Economic Catch Up”, professor of Economics at the Seoul National University, Keun Lee (2019) corroborates Romer Paul’s views and advances trenchant insights particularly on the paradox of the economic catch up. Lee puts forward cogent concepts for economies that he classifies as late comers, a descriptor that fits most African economies by and large. By premising his thrust on the two pillars of technological innovations and organizational innovations in economics, Lee frames a potent developmental framework built on the catch-up paradox.

He aptly states, “While catch-up means closing the gap between latecomer and forerunner economics, the catch-up paradox posits that catching up cannot be attained if the one merely continues to “catch-up” or imitate the forerunners”. (Keun Lee, 2019). This highlights the fact that developing countries need to think outside the box and seek to “catch-up” via means that leapfrog typical developmental traps.

Before the paper delves into the inefficacies of isolated economic growth in addressing the problem of poverty in Africa, there is need to characterize the causes of poverty in Africa.

While causes of poverty in Africa are multiple and complex, below is an outline of the prominent causes. The list is far from exhaustive.

Salient Causes of Poverty in Africa

Corruption and Poor Governance

It is not surprising that atop the list of causes of poverty in Africa is corruption as well as its concomitant evil of poor governance. Across the continent, corruption has seen the hollowing out of public institutions. The net outcome of this is that resources ring fenced for the benefit of the masses land in the pockets of the few elite in the higher echelons of government.

Resultantly, programs that are crafted to fight the scourge of poverty are at best, not fully implemented and at worst, derailed by a few corrupt individuals. Needless to say, a sustainable fight against poverty necessitates the existence of strong institutions that will foster an equitable distribution of resources. This can only be in place if there are non-corrupt governments in place that efficiently articulate a pro-development mandate and apprehend the corrupt. Without such transparency and integrity in governing institutions, economic growth remains stunted at best and where it does obtain, its benefits do not percolate to the masses.

Poor Land Utilization

The reality of poor land utilization has been cited in many fronts as both a result of, and driver of sustained poverty in the continent. In the great part of the content, people generally own large pieces of land which in most cases, are underutilized at best or lie fallow at worst. Part of the problem is that most land owners are not capacitated in terms of knowledge and resources requisite to draw significant value out of the land. In many cases, land owners simply use the land for subsistence and the greater value of the land is not realized in form growing cash crops that can be taken to market and empower the land owners to push the boundaries of their standard of lives while impacting positively on economic growth. Fostering economic growth without practical means of holistically empowering the masses with means to participate in the mainstream economy through making the most of the resources available at the grass roots level has not yielded any meaningful outcomes in any economy.

Wars and Conflicts

The spectrum of the main causes of poverty in Africa is not complete without mention of the pandemic of unending wars and conflict. In Africa, electoral fraud, military take overs and civil wars are common place. Intranational as well international conflicts and wars are also common in the continent. It is therefore not surprising that most countries involved in wars and unending conflict have little to show for advancement in all frontiers, and particularly in the arena of poverty reduction. War zones are practically unproductive and in any environment where safety and security are not guaranteed, investors who are critically needed to stimulate economic growth and potentially create jobs that can get people out poverty are kept at bay.

Poor Infrastructure

A great part of Africa has significantly poor infrastructure. The continent is generally characterized by poor roads, water systems and rail ways. Needless to say, these are major drivers and enablers of economic development. This has resulted in development in urban settings eclipsing development in rural areas. It is important to note that in most African countries, rural populations are significantly higher than urban populations. The era of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4iR) for example, holds many prospects and promises for Africa but without basic infrastructure most rural communities will be further marginalized in this era of technological disruption.

Disease and poor health care infrastructure

The adage that references the twin evils of disease and poverty is synonymous with Africa which is dogged by poor health systems and poor health care infrastructure.

The prevalence of various pandemics such as HIV/Aids, TB, malaria, ebola etc is worsening the development outlook of Africa. Pandemics rob African economies of the vibrant contributions of the active segments of the population. Diseases also necessitate the diversion of resources that would have been channeled into advancement and development into treating the sick. The high levels and frequencies of disease in the continent inevitably translate to higher mortality rates. In most households, the bread winners are lost to disease and death or other forms of incapacitation leaving their dependents marooned in abject poverty and thus perpetuating the vicious cycle of indigency.

The milieu of the main causes of poverty in Africa outlined above, inter alia, is further compounded by the reality of acute income inequality. The welter of factors culminates in an environment where the potency of economic growth to reduce poverty is significantly diminished.

The inefficacies of economic growth in reducing or eradicating poverty in Africa are largely rooted in the grim realities of income inequality. Income equality as a concept is quite oxymoronic in the sense it denotes economic inequality, i.e “..disparities in the distribution of wealth and income within or between populations or individuals. Distribution of wealth, comparison of the wealth of various members or groups in a society.” (Arcaya, Mariana C et al, 2015)

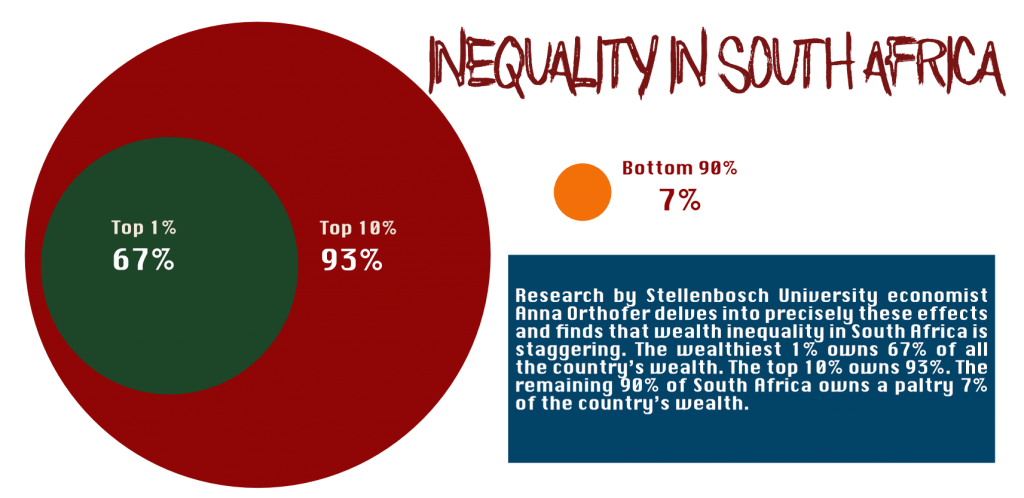

According to a 2018 World Bank report, South Africa is the World’s most unequal country. From the data that World Bank has for 149 countries, South Africa scored the highest (63) on a scale of 0 to 100 where 0 represents total equality.

“The country was very unequal in 1994 [at the end of apartheid] and now 25 years later South Africa is the most unequal country in the world,” says Victor Sulla, a senior economist for the World Bank in charge of southern Africa. “There is no country that we have data about where the inequality is higher than South Africa.” (Jason Beaubien 2018)

The 2018 report by World Bank indicates that: “…the top 1 percent of South Africans own 70.9 percent of the nation’s wealth. The bottom 60 percent of South Africans collectively control only 7 percent of the country’s assets.” (ibid, 2018)

What makes the outlook grimmer is the contemporaneous problem of income inequality which is wealth inequality. Wealth inequality denotes the imbalance in the income spectrum for those those classified as wealthy. For example, the income gap between a real estate mogul in a thriving metropolitan and that of a small scale farmer in some peri-urban vicinity is in most cases, staggering.

Income inequality in South Africa is microcosmic of the general imbalance across many economies in Africa, as an example, Namibia, Botswana and Zambia, are ranked as the second, third and fourth most unequal economies in the world respectively. The United Nations Development Programme Regional Bureau for Africa (2017) attests, “Although the average unweighted Gini for SSA declined by 3.4 percentage points between 1991 and 2011, SSA remains one of the most unequal regions globally. Indeed, 10 of the 19 most unequal countries globally are in SSA and seven outlier African countries are driving this inequality.”

The huge income disproportions fundamentally mean that economic growth will have diminished to no impact in reducing poverty in low to middle income economies.

Matilda Dahlquist (2013) in her thesis raising the question: “Does Economic Growth reduce Poverty?“, conducted an empirical analysis of the relationship between poverty and economic growth across low-and-middle income countries with Brazil as the main focus. Employing empirical cross-sectional regression, and exploring the tenets of Dual Economy and Human Capital theoretical frameworks, Dahlquist articulates the dynamics that cause poverty to obtain in the context of economic growth.

The scholar’s findings go at length to corroborate the view that economic growth does have a direct relationship with poverty reduction, however when the income inequality is pronounced, economic growth hardly translates to poverty reduction.

“The main conclusion from the empirical results is that economic growth does indeed reduce poverty. Also the level of poverty is strongly related to decrease of poverty, in such a way that a high level of poverty is associated to a slow decrease of poverty. However, economic growth does not appear to be sufficient a tool when the level of extreme poverty is high, suggesting that well-designed policies and investments in education are needed to obtain an inclusive, pro-poor growth and thus reduce the level of extreme poverty.” (ibid,2013)

In view of the above, it is arguably that economic growth alone cannot be upheld as a remedy for the plague of poverty in Africa. What is sticking out from various empirical excursions is that the pace and nature of economic growth are fundamental to the goal of reducing poverty.

It is therefore incumbent that strategies for eradicating poverty be premised on the effective strategies for fostering sustainable and inclusive growth. The perennial challenge for economists and policy makers is to strike a balance between growth stimulating policies and policies that will enable the poor and the marginalized to participate in the mainstream economy.

In light of the foregoing, there are three policy review areas that should be spotlighted, the need make labour markets work better, the need to extirpate gender inequalities and the need to foster financial inclusion (financial empowerment and banking the unbanked).

It is clear that the war against poverty can only be waged successfully through the efficacies of strong institutions, coupled with equitable distribution of resources. This requires non-corrupt governments. It is encouraging that the newly crafted international policies such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) in Africa have become attune to the important impact of politics on local economies and have thus placed much emphasis on transparent and accountable government, public resources management, free and fair elections, rule of law and active civil society.

It is high time that conventional disciplines of developmental economics are disrupted by robust and multidisciplinary models of pro-development economics characterized by transdisciplinary pedagogy. With such radical approaches to developmental economics, there is realistic hope that the dream to transform African economies into thriving development states, marked by substantively improved quality of lives, can be realized.

References

- Alex, Addae-Korankye. “Causes of Poverty in Africa: A Review of Literature” American International Journal of Social Science (2014) (http://www.aijssnet.com/journals/Vol_3_No_7_December_2014/16.pdf)

- Lee Keun. “The Art of Economic Catch-Up: Barriers, Detours, and Leapfrogging In Innovation Systems”, Lee, Keun (2019), 10.1017/9781108588232

- Bjork, Gordon J. (1999). “The Way It Worked and Why It Won’t: Structural Change and the Slowdown of U.S. Economic Growth”. Westport, CT; London: Praeger. pp. 2, 67. ISBN 0-275-96532-5

- The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Department for International Development, “GROWTH: BUILDING JOBS AND PROSPERITY IN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES”. (https://www.oecd.org/derec/unitedkingdom/40700982.pdf)

- Romer, Paul. “Endogenous Technological Change.” Journal of Political Economy 98, no. 5 (1990): S71–S102.

- “Statistics on the Growth of the Global Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2003 to 2013”, IMF, October 2012.

- Matilda Dahlquist. “Does Economic Growth reduce Poverty? An Empirical Analysis of the Relationship between Poverty and Economic Growth across Low-and Middle-income Countries, illustrated by the Case of Brazil”, Södertörn University, 2013 (http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:747531/FULLTEXT01.p)

- Dani Rodrik. Globalization, “Institutions and Economic Growth”, Harvard University One Economics, Many Recipes: (2007)

- Westover, Jonathan. (2008). “The Record of Microfinance: The Effectiveness/Ineffectiveness of Microfinance Programs as a Means of Alleviating Poverty.” Jonathan H. Westover. 12.

- Arcaya, Mariana C et al. “Inequalities in health: definitions, concepts, and theories.” Global health action vol. 8 27106. 24 Jun. 2015, doi:10.3402/gha.v8.27106

- Jason, Beaubien. “World Bank Estimate, South Africa Is The World’s Most Unequal Country”, 2018 (https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2018/04/02/598864666/the-country-with-the-worlds-worst-inequality-is)

- Investopedia. “Economic Growth”. 2019 (https://www.investopedia.com/terms/e/economicgrowth.asp)

- Economic and Social Inclusion Corporation. “What is Poverty”, 2008-2009. (https://www2.gnb.ca/content/gnb/en/departments/esic/overview/content/what_is_poverty.html)

- United Nations Development Programme, “Income Inequality Trends in sub-Saharan Africa, Divergence, Determinants and Consequences”, 2017. (https://www.undp.org/content/dam/rba/docs/Reports/undprba_Income%20Inequality%20in%20SSA_Infographic%20Booklet_EN.pdf)

A Developmental Economist.

ThinkTank

The core business of ThinkTank is to assert fundamental human rights across all societal fronts, through incisive and educative critiques on wide ranging socio-political and economic issues in Southern Africa, Africa and the world over.