A Critical Review of South Africa’s Nationally Determined Contributions (2021 Draft) to Climate Targets

- June 14, 2021

- Political Economics, Sustainable Development

Contents

INTRODUCTION

Climate change is a global crisis that confronts every living organism on the planet. The crisis is characterized by rising carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere as the nucleus of the calamity, caused largely, by fossil fuel burning related activities, deforestation leading to the global rise in temperature, ice melting in Greenland, rising sea levels and diminishing Arctic sea ice (Guardian, 2019). Like all countries in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), South Africa has expressed its commitment to fight against climate change in its mitigation and adaptation frameworks. The point of departure for the critical review of the NDC is that South Africa’s disposition to the climate crises is not ideologically neutral nor is it conceived in a vacuum. Applying a political-economic lens, the paper endeavors to spotlight the inefficacies of the countries disposition and position on climate change (as encapsulated in the National Determined Contributions, 2021) as well as the ideological flaws of the entirety of South Africa’s approach to climate change. Central to the treatise is problematizing South Africa’s blind, at best, or treacherous at worst; subscription to misleading United Nations driven Anthropocene-centered climate change doctrines, when “The UN has failed humanity and the planet” (Satgar, 2018). Ultimately, the aim is to proffer considerable alternative approaches to the fight against climate change.

The NDC understates and under-quantifies, qualifies the current climate change situation

The position of the Center for Environmental Rights (CER, 2021) is that South Africa’s “…revised climate plans are not ambitious enough”. The South African government however waxes self-congratulatory on imagined progress as can be gleaned from the NDC: “It is in this context that the update of our first NDC must be understood. The update represents a progression within our first NDC, and reflects our highest possible level of ambition, based on science and equity, in light of our national circumstances” (RSA, 2021). What the government misses is that any amendments on the 2015-2016 NDC is no mark of progression since the inchoate NDC framing itself is flawed. Nothing in the updated NDC speaks to the Climate Debt that South Africa holds on the continent when South Africa is, “…the worst polluter and most industrialized country” in Africa which bears “…an important obligation to accelerate its efforts to cut GHG emission reductions” in a bid to meet its national, continental and international legal obligations for securing climate justice and just transition (CER, 2021).

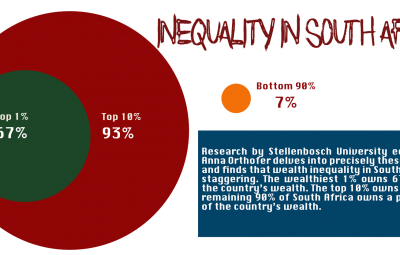

SAFTU concurs, “If we calculate our own economy’s emissions per unit of economic output per person, we find only Kazakhstan and the Czech Republic are higher, for countries above 10 million population. Our historic climate debt to the rest of Africa should be obvious” SAFTU (2021). The source goes further to reference extremely high elite driven emissions compared to measly carbon footprints of those living below the poverty line. The foregoing attests to gross underplaying of South Africa’s hand in breaching climatic boundaries and impacting negatively on the environment. South Africa’s position can be characterized as blasé considering that the country is, “…currently 14th on the world’s list of largest carbon emitters and is reportedly responsible for almost half of Africa’s greenhouse gas emissions, largely due to its heavy reliance on coal as an energy source” (SAFTU, 2021).

Considering, “…global coal use in electricity generation must fall by 80% below 2010 levels within less than 10 years” (CER, 2021), and the dire effects the climate crisis holds for the most vulnerable groups, the updated NDCs present no commensurate sense of urgency and ambition.

The Political-Economic Framing of the NDC

Applying a political-economic lens affords granularity in unpacking the deeper foundations of South Africa’s deficient approach to climate change. This will unearth the implicit choices the country’s policy regime is making through its climate change mitigation and adaptation stance and expressed in the updated NDC. Since the dawn of democratic South Africa in 1994, South African government embraced a neoclassical macro-economic framework. The Neoclassical mold of economics and its implications on governance hinges on the doctrine of supply and demand as the drivers of production, pricing, and consumption of goods and services” (du Toit et al, 2014). The heart of the disjuncture between neoclassical macroeconomics and reality is that the neoclassical approach notwithstanding its pedagogical allure, (Scerri, 2008), abstracts, albeit hideously, from history and socio-political factors of society. The neoclassical macro-economic outlook positioned the democratic government to embrace a global-financial-markets focused approach to governance and development. Unwittingly, the choice made in this regard was to pander to the whims and caprices of Global North capitalism at the expense of the people of South Africa.

du Toit et al (ibid) notes as a case in point that when South Africa’s economic borders were opened at the fall of apartheid, “21 Billion Foreign capital flowed into SARB at independence 1994”. This placed South Africa in a position where the economy experienced the double whammy of a white monopoly capital dominated economy internally, and a white foreign capital dominated economy externally. On a long-term trajectory, this has placed South Africa as an emissary of the West as is reflected in the countries developmental and climate policy regime. As Satgar (2018) observes cogently, “In South Africa, on 29 August 2016, the Commission officially adopted the Anthropocene as a new geological epoch within the Earth’s history, subject to scientific markers of this period being verified.”

It is important to note that the anthropogenic discourse in the IPCC’s represents a paradigmatic shift from the Marxist ecological framing or eco-socialism that was reflected in the ideology of the Kyoto Protocol. Satgar (ibid) makes this observation as well and reiterates that the Kyoto Protocol entails “…a need for Annexure A countries, the industrialized countries, to lead the way in cutting carbon emissions as part of affirming the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities” (Satgar, ibid). The scholar makes a compelling case for a shift to “Capitalocene” from Anthropocene (or the anthropogenic) centered approaches to climate change which cast climate change as a collective human-causality as well as a scientific issue, and thereby letting capitalism off the hook.

As evinced in the NDC, South Africa has imbibed the Anthropogenic ideology of the IPCC which affirmed in 2007 that “…human induced climate change’ is a scientific fact; hence humans are responsible for climate change” (Satgar, ibid). Regrettably, with this position the South African government is choosing capitalism (which assumes continued consumption as an inalienable constant even in the green shift), over radical transformation envisaged to deliver socio-economic equity and sustainable development. The Anthropocene narrative is a ploy to socialize the effects of capitalism while its gains remain privatized. Hickel’s (2020) observation is apt: “The Global North is responsible for 92%” of global emissions, not “every human being” as tacitly implied in the Anthropocene-centered narrative.

To this end SAFTU concurs, “…capitalism was the cause of global warming, climate change and the destruction of ecosystems. He [Vavi] said workers should not pay the price for their bosses’ irresponsibility by losing their jobs in mines and power stations, because of handing over power generation to IPPs” (SFATU, 2018). The point can be made at this juncture that South Africa’s response to climate change is bound to fail on many levels as it informed by a misdiagnosis of the climate change malady.

Meeting the 2030 targets and the Prospects of Just Transition

Emissions

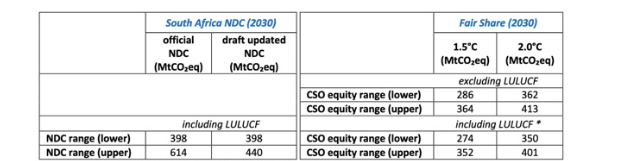

The Department of Forestry, fisheries and the Environment understates the problem of carbon emissions and subsequently understates the extent to which South Africa must go in reducing its national carbon emissions. Determinations by IPCC (n.d.) are that carbon emissions must be urgently reduced by about 45% within the 2010-2030 period, which leaves the world with just over 9 years to achieve that. The is the envisaged aim of the Paris Agreement of keeping global temperature below 1.5 degree Celsius “…confirmed by the IPCC as the tipping point for our climate” (CER,2021). While the updated 2021 NDC accepted the position of the IPCC on the overall target of carbon emission reduction, the NDC indicates that South Africa’s fair share range, on a 1.5°C pathway would be 286-364 MtCO2 when the proposed target threshold is 398 and 440 Mt CO2e. (CER, 2021)

The figure below presents the analytical comparison of the NDCs range against the fair share of 1.5°C and 2°C global pathways.

Figure 1: South Africa NDC range versus fair share of 1.5°C and 2°C global pathways

Source: (CER,2021)

CER (2021) calculates the NDC fair against the globally determined lower end fair share of 1.5°C

The fair share and the upper end 2°C pathway. Analysis indicates that the 1.5°C fair share warrants about 1½ times as much mitigation effort globally in 2030 (31GtCO2eq) while the 2°C (21GtCO2eq) below a baseline of 57 GtCO2eq. This comes against the backdrop of ostensibly bold claims made by government: “South Africa has developed policies in key sectors on mitigation and adaptation focused on both reaching climate goals and ensuring a just transition in which no-one is left behind.” (RSA,2021)

South Africa’s commitment to the just transition must begin with the praxis of the principle of equal per capita access to atmospheric commons. (Hickel,2020) This principle undergirds the novel approach by Hickel (ibid) to “…quantify national responsibility for damages related to climate change by looking at national contributions to cumulative CO2 emissions in excess of the planetary boundary of 350 ppm atmospheric CO2 concentration.” The logic is that South Africa must appreciate the gravitas of the fact that it has the biggest carbon emission footprint continentally thus it must bear a greater responsibility for climate damages in Africa.

Just transition

Due to ideological faults in NDC approach to the climate crisis, the envisaged just transition, which denotes, “…a range of social interventions needed to secure workers’ rights as economies transition from fossil fuel to renewable energy” (OECD,2017) will remain elusive. South Africa’s governance and developmental approach is married to capitalism wherein it is not possible to imagine thriving livelihoods with life capabilities (in Amartiya Sen’s capabilities approach) outside the prism of Capital, Labor and Productivity. As such the much-vaunted just transition is highly attainable. As a case in point: Eskom is building the Medupi and Kusile coal-fired power stations that are poised to be completed in 2023 and likely to have life spans of about 10 years when on the other end there are 2030 NDC targets to be met. On the other end, there are reports of Minister of Mineral Resources Gwede Mantashe’s Neo-Apartheid Landgrabs where communities will be effectively denied their rights to consent to the opening of mines in their communities (SAFTU, 2020), contradicting the principles of Bio Cultural Protocol, Prior Consent, and Benefit Sharing provisioned in the recently enacted 2019 Indigenous Knowledge Act (DST, 2020). From an employment creation point of view, SAFTU is clinical in spotlighting cheap job-creation politicking: “SAFTU rejects the minister’s false narrative that IPP’s will create 61 000 jobs. Most existing renewable energy companies do not employ many workers, when compared to Eskom, and do not offer the same salaries, benefits or improved working conditions,”.

The plans (contested in court by NUMSA and Transform SA) to privatize energy generation from renewable sources to Independent Power Producers (IPPs) is another ploy to keep lucrative economic opportunities to the capitalistic elite while keeping a majority of black South Africans in the margins of mainstream economy and undercutting the prospect of just transition.

Alternative Approaches

Capitalism must be recognized as the nucleus of the climate change crisis as well broader socio-political and economic woes of modern society. As Empson (2021) observes: “Capitalism’s innate drive to accumulate leads to resource depletion, pollution and human suffering.” Sadly, mainstream and UN driven climate change strategies are capitalistic in their framing.

The socialist approaches to climate change are a breath of fresh air. There is a caveat, however. While critiquing socialist approaches and locating them across the left to right political-ideological spectrum, Empson (2021) is disillusioned about some Anti-capitalist environmentalism of the left-most (Kate Aronoff’s and Mathew Lawrence and Laurie Laybourn-Langton). “There is a tendency to see neoliberalism as the problem, rather than the way that capitalism itself functions…” Climate change solutions must move away from trying to reform capitalism and build socialism from inside, whereas “…the system itself organizes to prevent this” (Empson, 2021).

Therefore, alternative solutions must take a form of decoloniality informed by an epistemological break from the capitalistic Anthropocene-centered misdiagnosis of the climate malaise. Just transition is one such alternative which can work as an antidote to the sweeping threats of climate change and environmental damage, but only if it is predicated on the radical concept of universal equity such as the Universal Basic Income Grant (UBIG). The solution must also be succored on Indigenous values systems such as Ubuntu (Terreblanche is Satgar, 2018) and other indigenous knowledge systems.

Just transition must be premised on affording everyone a decent life outside work hence the “universal” in the UBIG concept. This sufficiently and immediately dislodges the foundations of capitalism which thrives on, “entrapping growing numbers of workers in a dire predicament of survival.” (Marais in Satgar, 2018) This eco-socialist, democratic socialist disposition finds resonance in SAFTU’s framing of how alternative solutions should look like for South Africa: “Vavi said they agreed with NUMSA’s view that the path to a low carbon economy had to be based on worker-controlled, democratic social ownership of key means of production and means of subsistence. “There is a need for long term collective planning of wealth and production and how needs are met.” (SAFTU, 2021)

In making a case for the UBIG by spotlighting the unsustainable ecosystem of capitalism marked by diminishing investment in labour, declining wages, jobless growth, instability in the informal sector, Marais (ibid) asserts: “UBIG, rare among redistributive interventions, holds great transformative potential and challenges core tenets of capitalist ideology.” (Marais, ibid)

Conclusion

South Africa must think outside the box of the market oriented capitalistic economic paradigms that serve and service capitalism to the sustained systemic socio-economic detriment of the masses. There must be a willingness to raise difficult questions about the meaning of life and to question the perpetually enslaving concept of work that functions as the political springboard for the job-creation mantra and sloganeering.

In approaching sustainable development, South Africa must move beyond casting the triple evils of poverty, inequality and unemployment (RSA, 2021) as the foundation of socio-economic woes of society. To get to the root of the problem, South Africa must ask the ultimate question and acknowledge these triple evils as pillars of the problem and not the foundation of it. The ultimate question South Africa must ask is, “What is the foundation of poverty, inequality and unemployment?” Only then will the hideous monster of capitalism emerge as the root cause of socio-economic problems that not only South Africa faces but the whole wide world. Until then, the country’s climate change framework is pitched at managing the problem as opposed to eliminating it, on a broader scale the UN Sustainable Development goals remain unattainably utopian and, “The World Is Not Going To Halve Carbon Emissions By 2030” (Pielke, 2019).

References

CER.2021.COMMENTS ONSOUTH AFRICA’S DRAFT UPDATED NATIONALLY DETERMINED CONTRIBUTION UNDER THE PARIS AGREEMENT. (Available: https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/CER-Comments_Draft-Updated-NDC_30-April-2021.docx.pdf) [Accessed 31 May 2021]

DST.2020. Biocultural community protocols to help address injustices of the past. (Available:https://www.dst.gov.za/index.php/media-room/latest-news/3193-biocultural-community-protocols-to-help-address-injustices-of-the-past) [Accessed: 3 June 2021]

du Toit Charlotte,Moolman Elna .2014. A neoclassical investment function of the SouthAfrican economy. (Available: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/3661/DuToit_Neoclassical(2004).pdf;jsessionid=BBF298529C849E894F9B0DD08DAF163D?sequence=1) (Accessed: 25 May 2021)

Empson Martin. 2021.Four competing views on how to save the Earth. Climate & Capitalism. (Available: https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/05/28/four-competing-views-on-how-to-save-the-earth/) [Accessed: 3 June 2021]

Faulkner Neil. 2021. Covid, Climate, and ‘Dual Metabolic Rupture’. (Available: https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/05/26/covid-climate-and-dual-metabolic-rupture/) [Accessed: 2 June 2021]

Guardian. 2019. The climate crisis explained in 10 charts. (Available: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/20/the-climate-crisis-explained-in-10-charts) [Accessed: 3 June 2020]

Hickel Jason. 2020. Quantifying national responsibility for climate breakdown: an equality-based attribution approach for carbon dioxide emissions in excess of the planetary boundary. (Available: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30196-0/fulltext) [Accessed 1 June 2021]

Kenton Will.2020.Neoclassical Economics. (Available: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/n/neoclassical.asp) [Accessed: 2 June 2021]

OECD.2017.Just Transition. (Available: https://www.oecd.org/environment/cc/g20-climate/collapsecontents/Just-Transition-Centre-report-just-transition.pdf) [Accessed: 3 June 2021]

Morgan, Jamie. (2015). The meaning and significance of neoclassical economics.

NPC. 2011. National Development Plan 2030: Our Future -Make It Work. Pretoria: National Planning Commission, The Presidency, South Africa. https://www.brandsouthafrica.com/wp-content/uploads/brandsa/2015/05/02_NDP_in_full.pdf.

Pielke Roger. 2019. The World Is Not Going To Halve Carbon Emissions By 2030, So Now What?. (Available: https://www.forbes.com/sites/rogerpielke/2019/10/27/the-world-is-not-going-to-reduce-carbon-dioxide-emissions-by-50-by-2030-now-what/?sh=1c80ffa03794) [Accessed: 4 June 2021]

RSA. n.d. “South Africa’s Intended Nationally Determined Contribution (INDC). Online 25 September 2015.” Pretoria. http://www4.unfccc.int/submissions/INDC/Published Documents/South Africa/1/South Africa.pdf.

RSA.2021.South Africa’s First Nationally Determined Contribution under the Paris Agreement. (Available: https://www.environment.gov.za/sites/default/files/reports/draftnationalydeterminedcontributions_2021updated.pdf) [Accessed 31 May 2021]

SAFTU.2020.SAFTU endorses the Urgent need for Environmental Justice, Land Nationalisation, and The Right to Say NO! to Mining. (Available: https://www.polity.org.za/article/saftu-endorses-the-urgent-need-for-environmental-justice-land-nationalisation-and-the-right-to-say-no-to-mining-2020-06-02) [Accessed 4 June 2021]

SAFTU.2021.SAFTU SALUTES THE LABOUR AND SOCIAL ACTIVISTS OF OUR CONTINENT ON AFRICA DAY.(Available: https://saftu.org.za/saftu-salutes-the-labour-and-social-activists-of-our-continent-on-africa-day-25-may/) [Accessed: 31 May 2021]

Satgar, Vishwas, et al. Climate Crisis, The: South African and Global Democratic Eco-Socialist Alternatives. Wits University Press, 2018. Project MUSE.

Scerri, Mario. (2008). Neoclassical theory and the teaching of undergraduate microeconomics. South African Journal of Economics. 76. 749-764. 10.1111/j.1813-6982.2008.00217.x.

A Developmental Economist.

ThinkTank

The core business of ThinkTank is to assert fundamental human rights across all societal fronts, through incisive and educative critiques on wide ranging socio-political and economic issues in Southern Africa, Africa and the world over.