The Making of the Apocalypse: Unraveling South Africa’s Detonating Socio Economic & Political Time Bomb

- July 18, 2021

- Political Economics, Politics & Society, Sustainable Development

“The catastrophe in Children of Men is neither waiting down the road, nor has it already happened. Rather, it is being lived through. There is no punctual moment of disaster; the world doesn’t end with a bang, it winks out, unravels, gradually falls apart.” (Fisher, n.d.)

Borrowing Mark Fisher’s words one can make for a sobering characterization of South Africa. A country reeling in the unnerving grip of violence and unrest driving the KZN and Gauteng provinces to the brink. Over 160 malls have been looted (across the KZN and Gauteng provinces) with some of these gutted almost irreparably. The death toll stands at 212 at the point of this write up, chances are high the number will go up. Small and medium enterprises that have some capacity to rebuild will bear the hardest brunt as most of these are either insured hardly or hardly insured. Infrastructure damage is running into billions. Most SMEs hardly have anything left to salvage and the prospect of recovery grows grimmer by the day. Medium and Large business have not been spared either. Some factories have been cremated; some warehouses ransacked at best, incinerated at worst. Supply chains have been severed with fuel queues stretching a number of kilometers in various areas in the KZN, the epicenter of the conflagration. The crisis has led to a shortage of essential food supplies and fuel in some parts of KZN and seven days on the only light at end of the tunnel is that of an oncoming train of seismic socio-economic ramifications. The scenes are appalling, dreadful and unprecedented in democratic South Africa. But just like the catastrophe in film, “Children of Men”, the crisis is neither confined to the past neither does it lie in the remote future. It is being lived through.

What started off as riots were triggered by the jailing of former president Jacob Zuma for contempt of court after defying a ConCourt order compelling him to appear before the Zondo state capture commission of inquiry. The umbrage, discourse and analysis about the upheavals have been characterized by the dichotomization of condemning the contemptible violent criminality and the exposition of the socio-economic context that undergirds the unrest. The schisms in analysis have compounded the state of confusion around what is really at play, how society and the state must react and respond and what the implications are for South Africa’s future. A comprehensive analysis is necessary for diagnosing the deep-seated drivers of this mayhem with a view to proffer robust and sustainable solutions. Acknowledging the confluence and intersectionalities of multiple factors leading up the current crises, this paper is interested in positing a political-economic lens in problematizing capitalist realism as the main driver of South Africa’s socio-economic apocalypse.

Contents

Historical Background

Bold determinations to usher South Africa into a new epoch of welfare and prosperity were the hallmark of the celebratory and triumphant zeitgeist at independence. “On May Day in 1994, a few days after being elected South Africa’s first black president, Nelson Mandela declared to domestic and international capital: ‘In our economic policies, there is not a single reference to things like nationalisation, and this is not accidental. There is not a single slogan that will connect us with any Marxist ideology.’” In the bid to appease white interest and palliate fears of a radical dispensation, Mandela’s gesture was a public disavowal of leftist economic ideologies. The impression created was that of ideological neutrality in policy, at least, or developmentalism at most, when what played out, as we can now observe in retrospect, was a covert capitulation to the tentacles of capital. Denouncing Marxism is the low hanging fruit of neo-colonialist and neo-apartheid macro-economic policy in efforts to court capital into an incestuous marriage between what should be people-centered developmentalism and market-driven neoliberal economic policy. Marxism is excoriated for the failure of socialism. What is omitted and conveniently so, is that while Karl Marx missed the mark on what the political-economic solutions and alternatives to capitalism should be, the sage was clinical in interpreting history through the lens of political-economic class struggles and problematizing the internal contradictions of capitalism.

When Mandela made the declaration, Shoki (ibid) notes, “The volte face was complete”. Predictably, this marked the adoption of market oriented (capitalistic) macroeconomic policies in South Africa’s quest for reconstruction and development. “It begins with the infamous lifting of decades old capital controls in 1995 and develops to South Africa becoming the most financialised economy in the Global South excluding Asia. If neoliberalism was born kicking and screaming in a Chile, it confidently strode into maturity in South Africa” (Shoki, ibid).

The conceptual cleavages in the discourse and analysis of the current crises in South Africa are a reflection of the deep-seated ideological paucities of democratic South Africa’s macro-economic policy regime. Right from the dawn of independence, South Africa resigned from moral duty to delink from the capitalistic neoclassical macro-economic hegemony of the Global North.

A significant corpus of the political and economic analysis, although spot on in pointing the finger to the unresolved evils of poverty, unemployment and inequality, fails to put the finger right on the pulse of South Africa’s socio-economic political malaise. There area various conceptual frameworks such as Corporate Governance, the New Public Management, etc that can be used to explicate South Africa’s situation. Nothwithstanding, the focus of this paper is spotlighting the capitalistic praxis of governance, as the heart of South Africa’s ANC led government failure to bring to material the deliverables of the social contract upheld in the ANC’s Freedom Charter and concretised in the adoption of the amended constitution in 1996.

Capitalist Realism: The Elephant in the Room

The dawn of independence in 1994, marked an important era in South Africa’s economy which in the apartheid years had been cordoned off from the global economy. Political independence did not precipitate economic independence as most of the levers of the economy’s control remained in the hands of domestic white capital. Add to that, the composition of Foreign Direct Investment was largely Western capitalistic in its provenance.

“21 Billion Foreign capital flowed into SARB at independence 1994” Elna Moolman et al, (2004) state. The net implications of this have been a democratic economy that was neither delinked from the extraversion of the west nor disengaged from domestic capitalistic legacy. This has kept South Africa in the shackles of economic apartheid with an economy that is ultra-vulnerable to the so called “global” financial markets. This was evinced by the case of massive cash out flows (reversals) in face of recessionary global economy in 2008. To this dynamic Vavi, concurs, “To some extent, South Africa’s problems are overdetermined by global capitalism. A million workers lost their jobs between 2008 and 2009 when the impact of the world financial crisis reached our shores. Those jobs have not been replaced” (Vavi, 2021).

What is sad to note is that South Africa’s leadership (from the epoch of Nelson Mandela, Thabo Mbeki and Jacob Zuma, the supremo around whom the current unrest ensued, and the current head of state, Cyril Ramaphosa), has never been bold enough to adopt people-centered macro-economic ideology that is consistent with how a developing state must conduct itself. The state has consistently failed to take bold economic decisions in the fear of upsetting capital. This is not to say that the post-apartheid regimes have been an absolute no show, that would be inaccurate. The important factor is that developmental policies have been crafted in so far as they do not affect capital accumulation resulting in collateral failure by government to turn around the socio-economic fortunes of the masses.

Referencing Fredric Jameson and Slavoj Zizek, Mark Fisher reiterates that, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism”. That “reality” (our mental versions or illusions of the Real, [parenthesis supplied]) denotes capitalist realism: “…the widespread sense that not only is capitalism the only viable political and economic system, but also that it is now impossible even to imagine a coherent alternative to it” (Fisher, n.d.).

Neoliberalism as the Enabler of Capitalism in South Africa

Neoliberalism denotes political-economic structural and ideological ideas that emerged around the 1970s and 1980s. The key tenets of the ideology are: “…market orthodoxy, privatisation, deregulation, free trade, fiscal -austerity and reductions in government spending in order to restrict government involvement with and simultaneously boost the private sector’s role within the economy (Graham, et al, 2017). These approaches were a revival of the 19th century concepts of laissez-faire economic liberalism that had been popularized by reputed thinkers such as Friedrich von Hayek, Karl Popper and Milton Friedman, among others, who advocated extensive economic liberalisation and its key principles. The neoliberal movement was reinforced by the stances of Margaret Thatcher (1979-1991) and US President Ronald Reagan (1980-1988) who implemented a coterie of neoliberal reforms in the governments.

As soon as it came to power the ANC led government ran with a neo-Keynesian (public expenditure emphasis) people centered macro-economic framework, the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP). Among many deliverables RDP was aimed at addressing one of the legacies of apartheid, the rural-urban divide. Two years into democracy the ANC shifted from the pro-developmental RDP framework to the neoliberal and market driven, Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR). Heintz (in Sebake, 2017) observes that a depreciating rand, extremely low foreign exchange reserves characterized the environment for the policy shift. “The strategy proposed a set of medium-term policies aimed at the rapid liberalisation of the South African economy. These policies included a relaxation of exchange controls, trade liberalisation, ‛‛regulated” flexibility in labour markets, strict deficit reduction targets, and monetary policies aimed at stabilizing the rand through market interest rates.” (Heintz, cited in Sebake, ibid) GEAR was a macro-economic framework defined by liberalisation, deregulation and privatisation. What GEAR served to do was to simply wrestle economic power from the state and place it back in the hands of domestic capital with neoliberalism as the enabler.

Graham et al (ibid) elucidate succinctly the various forms that neoliberalism can take: Private Repossession (of national banks for example), restructuring of State-Owned-Enterprise (SOEs), Commodification (privatization and commodification of public assets primarily outside the capitalist system), as well as Privatized stimulus and represented by private public partnerships.

In South Africa’s post-apartheid government, these concepts have played into how the government has configured the macro-economic matrix through the restructuring of SOEs and the commodification of public goods, the commons, inter alia.

It is important to highlight the role of the International Monetary Fund and WorldBank in engendering state capitalism across the globe and particularly in post-colonial African states. These financial institutions impose economic structural adjustments as conditions for their loans. The heart of the conditions is shedding off most public service from the state to the private sector. “Moreover, debt-compromised nations are faced with the stark choice from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) that before any new development loans will be authorised, “structural adjustment” via privatisation and shrinking the role of the state is required” (Ellwood notes in Graham, et al, ibid).

Commodification of Public Goods

Water

The commodification of water as a public good in South Africa took shape early on the eon of democracy. Writing on “The Struggle Against Water Privatisation in South Africa” McKinley notes, “Following the neo-liberal economic advice of the WorldBank, the International Monetary Fund and various western governments (and heavy lobbying by private multinational water companies such as Suez and Biwater), the government drastically decreased grants and subsidies to local municipalities and city councils, and supported the development of financial instruments for privatised delivery” (McKinley, n.d.).

The foregoing pushed local government to adopt commercialisation and privatisation of basic services (public goods) in a bid to generate revenue that was no longer provided by the state. “Many local government structures began to privatise and / or corporatise public water utilities by entering into service and management “partnerships” with multinational water corporations.” (McKinley, et al)

This has led to a situation where the price of water has been inordinately higher in democratic South Africa that it was during apartheid. “Under apartheid (1993), the black townships around the Eastern Cape town of Fort Beaufort paid a flat rate of R10,60 for all services, including water and refuse removal. Under privatisation (Suez), from 1994 to 1996, the service charges were increased by 600% to R60 per month. A 100% increase in water connection costs was also imposed. In another Eastern Cape town, Queenstown, a similar picture emerged with a 150% increase in service costs. In the north-eastern city of Nelspruit (Biwater), where the unemployment rate hovers around 40% and average black household annual income is a paltry R1,2000, the price of water delivered to black communities increased by up to 69%! The cost recovery policy caused a national affordability crisis for black townships as well as rural communities” (McKinley, ibid).

The Mail & Guardian (2018) corroborates by citing water rates increases of up to 400% in Nelspruit between 1995 and 2000 after privatization. “In KwaZulu-Natal, changing a communal tap to a prepaid metering system caused a cholera outbreak that claimed 300 lives as people searched for alternative water sources” (The Mail & Guardian, ibid).

Energy

The market policies that govern Eskom have incapacitated the SOE to provide electricity as a public good efficiently to South Africa. As Rumney (2019) notes, the burgeoning household generator market masks the larger energy crises the country is facing. The ongoing process to unbundle Eskom into the components of generation, transmission and distribution is a move to parcel out some of Eskom business-economic matrix into private sector. Writing on the unbundling of Eskom as code for Privatisation, Sweeney (2019) is categoric, “First, unions and their allies in SA are correct: unbundling is about privatisation. It is a policy that comes straight out of the privatisation manuals of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).”

The strategic equity partners referenced in the unbundling strategy are players in the private sector who will provide capital. The continuous bailing out of Eskom while the government is looking for private investment in the transmission aspect of the unbundling (and perhaps in the generation aspect as well), is tantamount to selling new shares to a new investor. As Sweeney echoes, “There has not yet been an unbundling process that did not lead to incursions by the private sector into publicly provided electrical power”. (Sweeney, ibid)

Education

In education, multiple challenges that face the education systems have seen the discourse shift into rationales for the privatisation of education which detracts from upholding education as a public good. “Complex alliances and power blocs (of the Corporate Education Reform Movement) have formed across a number of countries that have increasing influence in education policy making (from driving testing, assessment, to providing curriculum, teacher training and credentialising, to school organisation models and packaged online curriculum). Their reach is extensive and transnational companies have begun to accumulate massive profits”. (Centre for Education Rights and Transformation (CERT), n.d) The observation by CERT (ibid) is cogent, “In reality the privatisation of education is the pursuit of a global ideological agenda rationalised on the ostensible (and often real) failure of governments to supply good quality public education to the majority of its citizenry.”

Security and Health

A case could be made for how the state is gradually parceling out various public services to the private sector. With regards to security, according to a Daily Maverick article in April 2018, the number of active private security officers, nearly half a million, is almost double the size of the SA Police Service and the SA National Defence Force. As such private security has grown to be a R45-billion industry.

On the health front, declining state of public healthcare, with the proposed National Health Insurance (NHI) far in sight, has driven the growth of private health care which is only accessible to the middle class, the affluent and privileged politicians.

Neoliberal Restructuring of SOEs

Amongst all democratic SA presidents, Ramaphosa has arguably been the architype of neoliberalist approach to economics. Since he came to office, there have been much of neoliberal approaches to the restructuring of state-owned enterprises. Eskom, the biggest State-Owned Enterprise by budget allocation, has always been governed by market-oriented policies and of late we have on the table efforts to unbundle the entity in a manner that will inevitably avail some of the entity’s value chain to the private sector. SAA has been privatized in a Private-Public sector arrangement where the state holds a minority stake.

Also, South Africa’s treasury has been faithful to the neoclassical economic script. The treasury has maintained a track record of public under-spending and austerity. This has been epitomized of late by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. In 2019 the official opposition, the Democratic Alliance (DA), praised Tito Mboweni’s medium term budget policy statement in October which had announced sweeping spending cuts.

Add to the foregoing, the Reserve Bank and StatsSA prop the neoliberal and capitalistic agenda by relying inordinately on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) calculations and evaluations of economic output. The GDP figures are vanity metrics that disregard the real object of economic policy, which is the betterment of livelihoods (economic development.) This is the reason why the United Nations has shifted from measuring economic development by GDP to the more comprehensive and people centered Human Development Index (HDI). South Africa has deliberately “missed that boat” in evaluating the country’s economic performance.

South Africa continues to project itself as a developmental state, but the policies implemented evince a conspicuous drift from the quintessential and instructive developmentalism of East Asia.

Effects of Privatisation

The effects of privatization include, but are not limited to, wrestling of the economic levers from the state to private interest which leads to the commodification of public-good. The neoliberal inspired cost-recovery model drives the prices of the commons up beyond the reach of a majority of the masses. Also, privatisation leads to massive job losses due private sector’s tendency to mechanize and cut back on labour over and above the profit maximising and cost minimizing nature of capitalism. The Mail & Guardian piece corroborates, “The choice to privatize should also take into account broader societal implications. One of the most damaging outcomes of privatisation is its effect on employment. According to the nonprofit organisation Public Citizen, privatisation of water services in the United Kingdom led to 10 000 job losses in 10 years. A decade after the UK’s miners’ strike of 1985, more than 200 000 jobs were lost as a result of coal privatisation, creating the largest British industrial conflict of modern times.” (The Mail & Guardian, 2018)

The collage of these implications leads to untenable social and economic outcomes particularly for developing economies. Not too long after the independence euphoria and zeitgeist of building a new era for South Africa, through neoliberalism; the country’s capitalistic macro-economic framework has gradually extinguished the prospects of prosperity and welfare.

A WorldBank reports details: “Although South Africa has made progress in reducing poverty since 1994, the trajectory of poverty reduction was reversed between 2011 and 2015, threatening to erode some of the gains made since 1994. Approximately 55.5 percent (30.3 million people) of the population is living in poverty at the national upper poverty line (~ZAR992) while a total of 13.8 million people (25percent) are experiencing food poverty. Similarly, poverty measured at the international poverty lines of $1.90 and $3.20 per person per day (2011PPP) is estimated at 18.9 percent and 37.6 percent in 2014/15, up from 16.6 percent and 35.9 percent in 2010/11, respectively” (WorldBank, 2020).

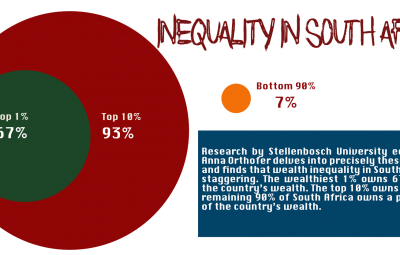

This has led to South Africa being among the most unequal societies in the world with a Gini coefficient hitting 63 in 2014/2015. A trajectory that has been consistent since 1994, rendering as a white elephant (Heintz in Sebake, 2017) the ANC bible, the Freedom Charter which declares, “the national wealth of our country, the heritage of all South Africans, shall be restored to the people” as one of its many commandments.

A cocktail of analyses have been proffered from across the wide political economic ideological spectrum in a bid to diagnose and proffer solutions to arrest the economic downturn. There are many who do not see capitalism as a whole, as the main driver of South Africa’s socio-economic and political woes. Industrial Development pundits such as Seeraj Mohamed, like many pundits, call for skin deep reforms of “our capitalism” to make it work. Writing for Polity, Mohamed comments, “As a society, we have to tackle the big questions. Ultimately, we have to decide on the type of capitalist system we want in South Africa” (Mohamed, 2010) Like many, Mohamed’s sentiments resonate with the views of many who acknowledge that capitalism has failed, and yet as far as these are concerned the solution still lies within capitalism as no other workable alternative is thinkable. The entirety of democratic South Africa regimes has not burdened itself to innovate outside the box of capitalism. All the much-vaunted solutions and policies crafted have been invented in the contrived omnipotence of capitalism. This attests to how macro-economic policy makers, academia and analysts can get hamstrung in the tentacles of capitalist realism, where the tacit assumption is that we have no other way but to make capitalism work because capitalism has been configured as the alpha and omega of political economics.

An honest analysis will reveal that capitalism is not a poorly or badly structured economic framework. Capitalism is not a demon possessed maniac the panacea for whom is exorcism. Capitalism is the devil that must be dispensed with in toto. Other political-economic analysts problematise neoliberalism (and rightly so), but mistakenly do so outside the wildebeest of capitalism as its vicious context. Some go as far as to suggest that the problem is that capitalism is not working properly in South Africa. But capitalism in South Africa is working just as it is calculated to work. To prosper the minority at the expense of the masses. Martin (ibid) argues: “Capitalism is a system with exploitation at its heart. Surplus value is extracted from workers’ labor forming the basis for the accumulation of profit. The capitalist state, far from a neutral set of institutions, organizes to protect the interests of capital.”

Economic Growth Versus Economic Development (Vanity Metrics)

What has been part of the travesty is that much of the economic fortunes that are celebrated are basically economic growth (GDP output) deliverables and not economic development (Betterment of Livelihoods) milestones. The fact that South Africa can have a booming stock market which hit the 47% mark since the slump of April 2020, in the context of a declining economy, attests to the obscenities of profit driven capital interests whose fortunes continue to burgeon as the inverse function of the constrained wages and impoverished masses. There are no surprises here since capitalism is quintessentially profit maximizing and cost (wages) minimizing.

Vavi’s diagnosis is apt: “To see a stock market boom during a real economic decline is sickening. Our economy is suffering from extreme Covid-positive capitalism: Coughing harshly, running a high temperature, in desperate need of respiration, and mostly killing poor and working people, especially those with darker skins” (Vavi, 2021).

Mainstream Media and the Neoliberal Agenda

The foregoing presents an arena where mainstream media generally misleads the public with economic growth inclined analyses that abstract from the bread-and-butter issues (socio-economic development of the masses) in the context of human development. The growth of stocks is hailed and valorized by media to paint a rosy economic picture. Skewed analysis only serves to delude South Africans and the whole world that the economy is doing well when the reality is to the contrary.

Mohamed corroborates, “Further, media coverage of economics is usually limited to short-term concerns, such as day-to-day changes in the exchange rate and the interest rate” (Mohamed, 2010). The foregoing characterizes not only the breeding environment, but also the incubator of South Africa’s unenviable socio-economic malaise.

Mainstream media has been a crucial enabler of the neoliberal agenda in South Africa. Brendan (2017) does a sterling work in exposing how the print media in South Africa has paved way for privatisation. The scholar’s work “…examines the responses of the mainstream media to these neoliberal initiatives, looking specifically at English-language newspapers and their coverage of water, electricity and waste management services. It explores the extent to which the print media can be deemed to be in favor of privatization as well as the more subtle, discursive ways in which it covers these issues” (Brendan, ibid).

The research found that corporate media in South Africa generates and perpetuate a neoliberal discourse on privatization and present the dialogue as monolithic and omnipotent. Brendan (ibid) states: “Nevertheless, it is exactly this façade of objectivity which gives neoliberalism its hegemony. By appearing to give equal space to different points of view there is a perception of balance in the press that obscures the more subtle, opinion-making discourses that generate neoliberal biases.”

Brendan’ findings resonate with Graham et al’s exposition of “The Dominance of Neoliberal Dis-course and the Death of the Public Good” in Ireland. Employing Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) by Wodak (2007) the researchers unearth, ” the transparent structural relationship of dominance, discrimination, power and control that is manifest in language”. (Graham, ibid) Similar to the South Africa’s context, the work by Graham et al found mainstream media content in “…both the volume and the thrust” to be inordinately “inclined to portray privatization in a favorable, non-critical light”.

Most of the content in mainstream media aligns with Neoliberal frames. “…with a competitive frame being dominant; essentially, the topic was treated from a market or business perspective rather than the perspective of the public good or wider society” (Brendan, ibid)

Business realism is a derivative of capitalist realism. In this doctrine, public services must be delivered in a business model if they are to be rendered efficiently. Public service is thus structured in business and consumer terms. Privatization is also posited as the only viable model for delivering public goods.

As Graham et al note, “ …the framing of privatisation as a business and consumer issue, rather than a political one or that of the public good, acts to detract from the political aspects of the appropriation of public assets by international capital, including the implications for infrastructure, economic development and accountability to democratic structures, none of which receive sufficient journalistic attention”.

Just like there are financial journalists, business journalists, legal journalists, health science journalists, etc, developmental economics and political economics journalism are critical skills in South Africa. Literacy in these crucial disciplines is critical for any developing economy. It will help curtail the wave of the neoliberal trumpeting hegemony that saturates mainstream media and help to frame a robust discourse from which formidable dialectic, as opposed to monolithic solutions can emerge.

The Making of the Apocalypse

As indicated earlier, South Africa is the most unequal society in the world by measure of Gini coefficient. “Increasing unemployment and economic inequalities associated with neoliberal policies have also pushed even more of South Africa’s population into the poverty trap” (Sebake, 2017). The inequality is characterized by three contours. It is raced (Whites have more wealth and income that blacks), it is gendered (males have more income and wealth that females), it is spatialized (classes living in high end suburbs have better income and wealth that the less privileged living is poor Living Standard Measure (LSM) settlements).

This is why for every Sandton there is an Alexander. The palatial utopia of the wealthy is consistently desecrated by the sight and the trespassing (nauseating to the privileged) of street hawkers mushrooming to eke out a living at random and inconvenient corners of these heaven-on-earth settlements boom-gated from the ugly and inconceivable conditions of poverty in South Africa.

Already simmering in the psycho-social and economic impact of Covid-19, with massive job losses, an adjusted lockdown level four (4), confining most South Africans to their hovels of squalor, hunger and pent-up anger, it was a matter of when not if, before the fuse would go off. All that was needed was a spark. The jailing of Jacob Zuma was that spark and the ruckus ensued. The counter-revolutionary, as the crises is being diagnosed, found the appalling socio-economic conditions as an expedient accessory that could be instrumentalized to drive, populate and capacitate the riotous revolt.

The Violent Nature of Protests

One of the distinctives of the recent protests has been the grotesque violent nature of lawlessness. In a study conducted by Global Peace Index (2018) South Africa came up as one of the most violent societies in the world. The sobering reality enjoins us to go beyond skin deep in condemning violence and to interrogate the reality further with a view to understand the roots of the phenomenon. The article by Maina (2020) which takes a sociologist’s perspective on what is behind violence in South Africa, references the work of a Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung who goes to great lengths in identifying three main sources of violence: direct, structural and cultural. Galtung’s work exposes that the horrifying nature of direct crime, such as murders, rape, violent uprisings etc are outcomes of structural violence that exists in form of systemic inequality and injustice. It is not hard map out the correlation between the failures of capital driven macro-economics and the high levels of systemic inequality that plays out in joblessness, poverty, violent crime and disillusionment, etc in South Africa.

Put these variables in the same place and time settings in the context of a crippling Covid-19 pandemic with its adverse psycho-socio and economic impact, then the ticking time bomb is ready to detonate. The notion that the unrest is a mere ethnic mobilization is a dangerous mischaracterization of the real drivers of the unrest. It would be foolhardy for anyone to conclude that the looters are looting because they are of a certain tribe. Tribe, caste or race have never been reasons for looting. Material conditions are the underlying drivers of the unrest. Once we establish that there is a politicization of poverty, the fact that the unrest may have taken root or have played out in some tribal optics and other dynamics is valuable but invalid in expositing the main conditions giving context to the uprising.

Maina’s treatise references the violent nature of the apartheid government which used state machinery to rule by violence and force as an important defining thread of the nature of violence in contemporary South Africa. The consistent and systemic use of institutionalized violence registered violence in the psyche of the society that violence is the way to solve problems. “Such a culture of violence is hard to stop, especially when it has become a legitimised and institutionalised form of coercion” (Maina, ibid) As hinted earlier, structural violence is what then plays out in various forms of direct violence such violent robberies, rape, murder, road rage, femicide, etc and the latest unrest characterized by aggravated damage of infrastructure, vigilantism, etc. Having failed on social and economic deliverables of democracy, the South African government response to unrest has consistently taken the form of catastrophism in dealing with symptomatic upshots of its failures. This has been marked by the unleashing of brute force to curtail civil instability. The deployment of soldiers in the Cape Flats, The Marikana massacre and the latest deployment of army and police to arrest the Zuma related unrest come to mind. Unfortunately, the trend continues to entrench the notion, in the psyche of citizens; that violence is the way things get done. While violence does warrant a drastic response from the state, the point to be made here is that government has all the resources at its disposal to champion the ideals of peace and prosperity and avoid running the country into a precipice that makes brute force necessary.

Weberian Conceptions of Corruption and State Capture

The jailing of Zuma, which sparked the violent unrest presents important dynamics about the South Africa’s political-economic setting. When Ramaphosa came into power he took a firm approach to confront corruption and particularly bring the king pins and pawns of the state capture project into book. The conceptions of state capture and corruption, by the state and political commentariat have largely been rudimentary. Political analysis must entail the rigour of contextualizing the phenomena of state capture and corruption, and the implications of a nuanced application of these concepts within South Africa’s developmental and political-economic context. The whole crusade against state capture has been flying on Weberian conceptions and universal assumptions of what state capture and corruption mean. Weberian notions of state capture and corruption are predicated on the assumption that state institutions are neutral and benevolent in their object to serve the masses. There is need to exegete the state of capture before one dives into state capture. In their invaluable work, (Re)conceptualising State Capture (Eskom Case Study) Godinho & Hermanus warn, “Any definition which presumes the moral legitimacy or benevolence of existing institutions cannot be applied consistently in countries in transition, where institutional transformation necessarily progresses over time.” (Godinho & Hermanus, 2018)

Robust political-economic debate and analysis must therefore stand up to these complexes particularly for a country like South Africa battling to transition from underdeveloped, through developing to developed. Whether or not the disregard of rule of law and the institutions of constitutional democracy have merit or not is beside the point. It is a critically important intellectual milestone for political economic research, theory and praxis to acknowledge the complexes that characterize the dissenting fraternity within the ANC whether or not one agrees with their ideology, or in fact lack it. Part of the reason the state downplayed the revolt and thus could not detect the revulsion nor be able to mount a timeous and commensurate response, was failure to grasp the complex political dynamics of the factional battles between Ramaphosa’s camp and the RET faction that are now holding the whole of South African at ransom.

Commenting on Zuma’s latching on the leftist ruse Shoki (ibid) observes, “That this is happening is not simply incidental or motivated by personal grievances but expresses serious disagreement between state officials and business elites about which accumulation strategy should rule the day.” In this pretext, Zuma’s repeated calls for “radical economic transformation” must be discerned as a contra-ideology to curtail white capital. “His crony-capitalist alternative offered routes for accumulation to the “excluded” in state-owned enterprises. Ramaphosa and his acolytes are best understood as longing for what can only be called, in their view, a more “civilised” or pure model of accumulation, one premised on the outdated assumption that markets and the state can be disentangled.” (Shoki, ibid)

The stakeholders of South African society need a literate navigation of these complexes. South Africa needs to delink from the Eurocentric conceptions of statecraft and state capture particularly in diagnosing the current crises and the dynamics that are being exploited to forment anarchy. Mainstream media has predictably lacked this analytical rigour. The numbing reality is that the ANC battles are not ideological battles about how best to serve the people of South Africa. The contestations are simply about which elite sector of society must benefit from perpetual capitalism, either the traditional white monopoly base as represented by Ramaphosa as a capitalist himself and his neoliberal administration, or the elite blacks, typified by Zuma, the capitalist cronyism (state capture) of his admin and the RET faction.

Superficial Public and Private Realms

Godinho & Hermanus, in their characterization of state capture bring to the fore the problematique of universalizing the distinction between private and public realms.

“Similarly, definitions that presume that some universal distinction between public and private realms can be applied consistently in transition and developing countries, encounter problems when applied in such contexts.” (Godinho & Hermanus, ibid) The observation by the scholars is apt for the South Africa’s context given the confluence of public players and private players as epitomized by Zuma’s tenure and the state capture apparatus as well as the station of Cyril Ramaphosa who is a head of state, and a billionaire business men.

“Whether in relation to the office, interests, or outcomes involved in corruption, a public/private dichotomy proves false in contexts where prevailing political ideology or culture makes no such distinction, where political actors are frequently also active in the private sector, or where the line between Weberian (impersonal bureaucratic) and traditional (family/community oriented) values has not been institutionalized or internalized” (Hoadley & Hatti, in Godinho et al, ibid).

In addition to the above mentioned, the following observation by the scholars is clinical particularly for South Africa: “Indeed, the prominence of “business-politicians and politician-businessmen” in the upper echelons of most, if not all, states should caution any definition of corruption or state capture that hinges on this dichotomy (Roy, 2017, Godinho and Hermanus, ibid).

This political-economic lens is crucial for exposing the political football that the ruling party is playing with the masses. A cul-de-sac self-serving game of thrones buttressed in crass ideological bankruptcy from all contending parties.

Rule of Law and Socio-economic Development

South Africa’s constitution in section 7(2) compels the state, to respect, protect, promote and fulfill a range of socio-economic rights as a matter of obligation. Which as a rule of law must be actualize (SAFLII, 2014). Over the years, rule of law in South Africa has been loud on individual rights and property rights and near silent on socio-economic developmental rights of citizens as enshrined in the Constitution.

“The core socio-economic rights impose more qualified positive obligations on the state as provided for by sections 26(2) and 27(2), to take reasonable legislative and other measures to ensure that the entitlements promised by the rights are progressively achieved” (SAFLII, ibid).

The disequilibrium in what provisions of the constitution society emphasizes and which ones it deemphasizes leads to the deteriolisation of the courts from serving as courts of justice to functioning as mere courts of law whose ultimate object diminishes from the holistic developmental and welfare (socio-economic rights) locus to mere abstract jurisprudential mechanics. This is often enabled by an emphasis of rule of law as disembodied from the body of the state and far removed from society. Rule of law must be applied across the board. Rule of law must span apprehending those who have acted unlawfully and equally hold the organs of state to deliver and account for their developmental mandate as it is encapsulated in the Constitution.

The Unjust Just Transition

Kriel in Emalahleni Mpumalanga was spotlighted as the second most polluted spot on earth via NASA satellite informatics. “The study found that Kriel in Mpumalanga, with its high concentration of coal-fired power stations, ranks as the second worst sulphur dioxide SO2 emission hotspot in the world” (Greenpeace, 2019) This is due to the over-concertation of coal mines and coal-based power stations in Mpumalanga. Kriel case is a tip of an icerberg of the grim state of capital driven environmental and climatic damage in South Africa. This means that SA is unlikely to meet the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) target of keeping global warming to 1.5˚C, but also the United Nations Sustainable Developmental Goals (SGDs).

With a turn-over of 10 CEOs in the past ten years, a debt of about R484bn, and no solid plan for energy just transition, Eskom is decommissioning certain power stations (Hendrina) while still building others Kusile and Medupi, whose completion is behind schedule, incurring budget overruns, and dysfunctional completed bits. Eskom is also characterized by soaring tariffs and chronic load shedding that puts South Africa in an untenable condition. The decommissioning of Hendrina in the scope of the just transition is resulting in massive job losses without any strategic plan to place the workers in other sectors. Former Finance Minister Nhlanhla nene fingered Eskom as the single largest threat to South Africa’s economy. State capture, corruption and rent seeking, mismanagement have hollowed out Eskom as a state enterprise.

Just transition is the call largely by labour unions for an equitable paradigm shift from fossil fueled based economies to economic bases based on renewables and low carbon alternatives. Central to the transition is the corrective dimension of giving economic agency to communities. As mentioned earlier, the policy position of government has been confined to dictates of capital. This has sadly crept into the framing of the just transition which is the single most promising paradigmatic shift into sustainable development for South Africa, at least on paper.

The neoclassical economic framework is presenting a double whammy where South Africa has an urgent need to address environmental justice (enshrined in the constitution), and social justice at the same time. This is what places Just Transition as the center piece of this hypothetical transition. What are the prospects of the materialization of the Just Transition? Regrettably, the SA government has imbibed the capitalistic framing of the climate change as an Anthropogenic (human driven) crises. The Anthropogenic (Anthropocene) theory of climate change is a scandalous variant of capitalistic jingoism whose calculus is to blame the entirety of humanity for environmental and climate damage and injustice through obfuscating the fact that it is rather capital (not the entire humanity) that is driving this world not only into a socio-economic cataclysm but also to an environmental catastrophe. The Anthropocene only serves to perpetuate the privatization of the loot by capital interest while socializing the damages. The notion is concocted that we are all responsible for climate change and its gory implications when the finger must be pointed squarely to capitalism. The coal mining sector (like many sectors of the economy), which is the biggest contributor to South Africa’s carbon footprint, is private player dominated. In a nutshell, the government is running with a capitalistic frame of Just Transition, which has been constricted as Just Energy Transition when the shift must be an economy wide paradigmatic shift to sustaible development. The contention to be made here is that any transition that is birthed in the labour wards of capitalism is inherently and inevitably unjust.

Analysis must not miss the fact that capitalism thrives and survives by making poverty necessary (in order to create cheap labour – modern day slavery), exclusion and power disbalance across the classes so as to feed the insatiable commodification of the have-nots by the haves. Over the years the sloganeering around the fight against, “poverty, inequality and unemployment” has become the buzz phrase of job creation politicking. The three social ills are cast as the three evils. Government hardly burdens itself with the question of what the real devil is behind these three evils. The devil is capitalism. “The capitalist state, far from a neutral set of institutions, organizes to protect the interests of capital.” (Martin, 2021)

How to Fix This (Conclusion)

South Africa’s looming apocalypse is an inevitable outcome of the regime of capital-driven, neoclassical macro-economic policy, which not only has a hefty human cost but unsustainable environmental and climatic implications. The fear in the recent decades has been that, “We don’t want South Africa to go the Zimbabwe way”. Valid as the fear is, analytical rigour that informs that observation must enjoin the leadership to find better models that can mid wife the transformation aspirations of South Africa. If that does not happen, what can be observed is the irony of making South Africa another Zimbabwe in the name of avoiding making South Africa another Zimbabwe. It matters not what direction South Africa is taking if the destination will be the same as where Zimbabwe is. What matters is that if the underlying issues of socio-economic justice are not addressed, South Africa is inevitably inching towards the same doldrums that so far, Zimbabwe has colorfully monopolized within SADC.

Neither the current framework for Just Transition nor the National Development Plan (NDP) address the fundamental problems of South Africa. As things stand, there is no sufficiently robust plan on the table for the government to put South Africa on a promising path that can realistically turn around the socio-economic fortunes of the country. Of course, there are isolated flickers of hope hither and thither, but nothing sufficient to dispel the pitch-dark nightfall that is slowly and yet rapidly; engulfing the nation.

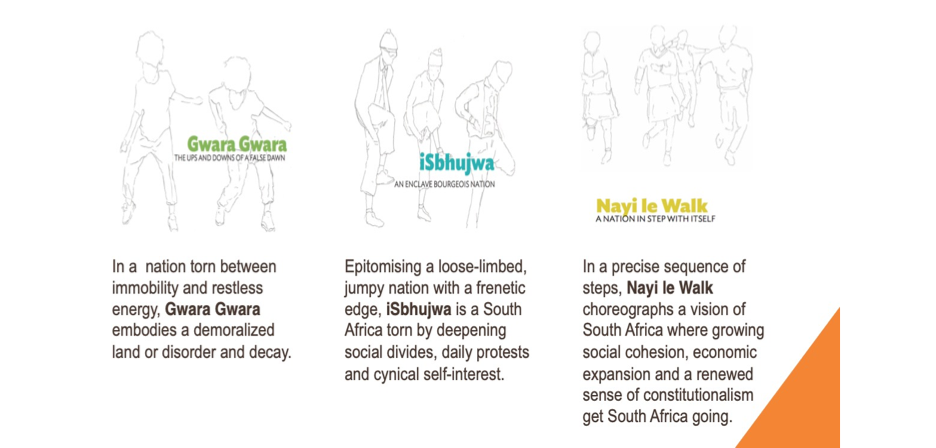

The sentiments by former statistician Lehohla Pali provide much needed comic relief although sobering: “South Africa is in the Gwara Gwara of the skedonk”, he quips. It is a matter of laughing in order not to cry, said Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

In the mold of shifting from the capital driven neoclasscial macro-economic policies to the heteredox multi-disciplinary approaches to economic development, Pali elucidates, “… the three paths of Gwara-Gwara which is a land of hopelessness and disorder, Isibujwa which is the trickle-down economics of Friedman and Nayi le Walk which provides a heterodox road map of South Africa towards a better future” (Indlulamithi, 2021)

Figure 1: The Three Indlulamithi Scenarios

(Source: Indlulamithi, ibid)

Pedantic ideology can easily clutter research and thought process and therefore the paper is cognizant of limitations of ideology. Notwithstanding, and at the risk waxing doctrinaire, the choice for the capitalistic lens was deliberate as it enabled the author a broad interpretive analysis of capital-inclined state policy, the inherently flawed nature of South Africa’s accumulation regime which is pernicious not only to the environment but to the humans. A Marxian analysis has also been crucial in unmasking the class struggles beyond race, between the haves and the have-nots, e.g. the RET formation which is a case of blacks seeking to usurp the transformational dream from fellow black masses. The paper has thus substantively demostrated how capital-inclined macro economics of the government of South Africa have failed the masses.

A follow up post will be a collaborative effort from various stakeholders to proffer comprehensive solutions and economic development pathways that can put South Africa on a different trajectory. In the meantime, the paper underscores the internecine nature of violence that destroys both the perpetrators and their targets. As such the current nightmare of all forms of violence and conflagrations across the country is condemned with no uncertain terms as untenable. The state must act swiftly and proactively in arresting not only the criminals but the entire inferno. That done, a paradigmatic shift in macro-economic policy is long over-due. A dialectic rather than dualistic debate must be raised by research and academia as well as broader society on what formidable alternatives can be innovated for efficient public service and a holistic upliftment of livelihoods. The government must divorce itself from capitalism. It must decide whether it wants to eradicate the problem or to simply manage it. Solutions must be innovated outside the binary of the current state of public service (that has been hollowed out by corruption and mismanagement) and the unsustainable neoliberal shedding of public service into capital interest through privatization.

The latest racial tensions in Phoenix have seen the resurfacing of the relics of the egregious Group Areas Act where a few shops that were still running were reportedly serving only White and Indian customers. This has shown that social cohesion and harmony will not be achieved outside the robust framework of restorative justice which must see a substantive refactoring of the distribution of resources, the land being the most critical. If the issues raised remain unaddressed, the military may have cleared the streets for now, but the socio-economic tremors are here to stay and it is a matter of when and not if, before another trigger goes off and another conflagration erupts. The condition of inequality puts the entire society in tenterhooks where the future is as uncertain for the blacks and non-white masses as it is for white South Africans. Consequently, the ideal of a “Rainbow Nation” remains a fallacious travesty that disgracefully sustains white privilege and class privilege for affluent non whites, while it continues to mock the destitution of the masses. Unless drastic measures are taken, the Rainbow Nation will remain an unreachable pie in a literal blue sky of an unfolding socio-economic and political apocalypse that mirrors the lived continuum of malady in “Children of Men”.

References

CERT.n.d Privatiosation of Schools: Selling out the Right to Quality Public Education For All. (Available from: https://www.uj.ac.za/faculties/facultyofeducation/cert/Documents/Privatisation.pdf) [Accessed: 18 July 2021]

Elna Moolman, Charlotte du Toit. n.d. A neoclassical investment function of the SouthAfrican economy. Elna Moolman. (Available from: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/3661/DuToit_Neoclassical(2004).pdf;jsessionid=BBF298529C849E894F9B0DD08DAF163D?sequence=1) [Accessed, 23 May 2021]

Fisher Mark.n.d.Capitalist Realism: Is There no Alternative. Zero Books.

GlobalPeaceIndex.2018.Measuring Peace in a Complex World. (Available from: https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/Global-Peace-Index-2018-2.pdf) [Accessed 16 July 2021]

Graham Ciara and Ilke Henry S.n.d.Framing Privatisation: The Dominance of Neoliberal Dis-course and the Death of the Public Good.

GreenPeace. 2019. Mpumalanga SO2 pollution as bad as NO2, new study finds. (Available From:https://www.greenpeace.org/africa/en/press/7678/mpumalanga-so2-pollution-as-bad-as-no2-new-study-finds/)

Godinho Catrina & Hermanus Lauren. 2018. (Re)conceptualising StateCapture-With aCase Studyof South African Power CompanyEskom. (Available From: https://www.gsb.uct.ac.za/files/Godinho_Hermanus_2018_ReconceptualisingStateCapture_Eskom.pdf) [Accessed 16 July 2021]

IOL.2021. Majority of local investors miss out on strong stock market recovery. (Available from: https://www.iol.co.za/personal-finance/investments/majority-of-local-investors-miss-out-on-strong-stock-market-recovery-78e5999f-a7d6-49ea-8404-dc82ad8dd2ee) [Accessed 12 July 2021]

Maina Julius. 2020. What’s behind violence in South Africa: a sociologist’s perspective. (Available from: https://theconversation.com/whats-behind-violence-in-south-africa-a-sociologists-perspective-128130) [Accessed 16 July 2021]

Martin Empson .2021.Four competing views on how to save the Earth. (Available from: https://climateandcapitalism.com/2021/05/28/four-competing-views-on-how-to-save-the-earth/) [Accessed 13 june 2021]

McKinley Dale T.n.d.THE STRUGGLE AGAINST WATER PRIVATISATION IN SOUTH AFRICA.(Available from https://www.tni.org/files/watersafrica.pdf) [Accessed 15 July 2021]

Mohamed Seeraj.2010. Capitalism in South Africa. (Available from: https://www.polity.org.za/article/xxx-2010-01-14) [Accessed 15 13 July 2010]

Pali Lehohla. 2021. SA on a Fork Road. Presentation for the Indlulamithi Scenarios Trust by the Centre for Leadership and Dialogue at GIBS.

Reg Rumney.2019. BUDGET 2019 OP-ED: Privatisation is inevitable in SA – but you may not recognise it. (Available from: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-02-21-privatisation-is-inevitable-in-sa-but-you-may-not-recognise-it/) [Accessed 16 July 2021]

Sebake BK. 2017.Neoliberalism in the South African Post-Apartheid Regime: Economic Policy Positions and Globalisation Impact. (Available from:

http://ulspace.ul.ac.za/bitstream/handle/10386/1860/sebake_neoliberalism_2017.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y) [Accessed 15 July 2021]

Sweeney Sean.2019. Unbundling Eskom is code for privatisation. (Available from: https://www.businesslive.co.za/bd/opinion/2019-02-15-unbundling-eskom-is-code-for-privatisation/) [Accessed 15 July 2021]

The Mail & Guardian.2018.Parastatals: Privatisation won’t solve the crisis. (Available from: https://mg.co.za/article/2018-02-28-00-parastatals-privatisation-wont-solve-the-crisis/) [Accessed 15 July 2021]

Vavi Zwelinzima. 2021. The real state of South Africa’s still-failing capitalist economy: Parasitic, super-speculative and unpatriotic. (Available From https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2021-06-08-the-real-state-of-south-africas-still-failing-capitalist-economy-parasitic-super-speculative-and-unpatriotic/) [Accessed 14 July 2021]

WorldBank.2020. Poverty & Equity Brief South Africa Sub-Saharan Africa. (Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/data/download/poverty/33EF03BB-9722-4AE2-ABC7-AA2972D68AFE/Global_POVEQ_ZAF.pdf) [Accessed 16 June 2021]

Men.

A Developmental Economist.

ThinkTank

The core business of ThinkTank is to assert fundamental human rights across all societal fronts, through incisive and educative critiques on wide ranging socio-political and economic issues in Southern Africa, Africa and the world over.